Story

Agnes Gund: Visionary Collector and Philanthropist

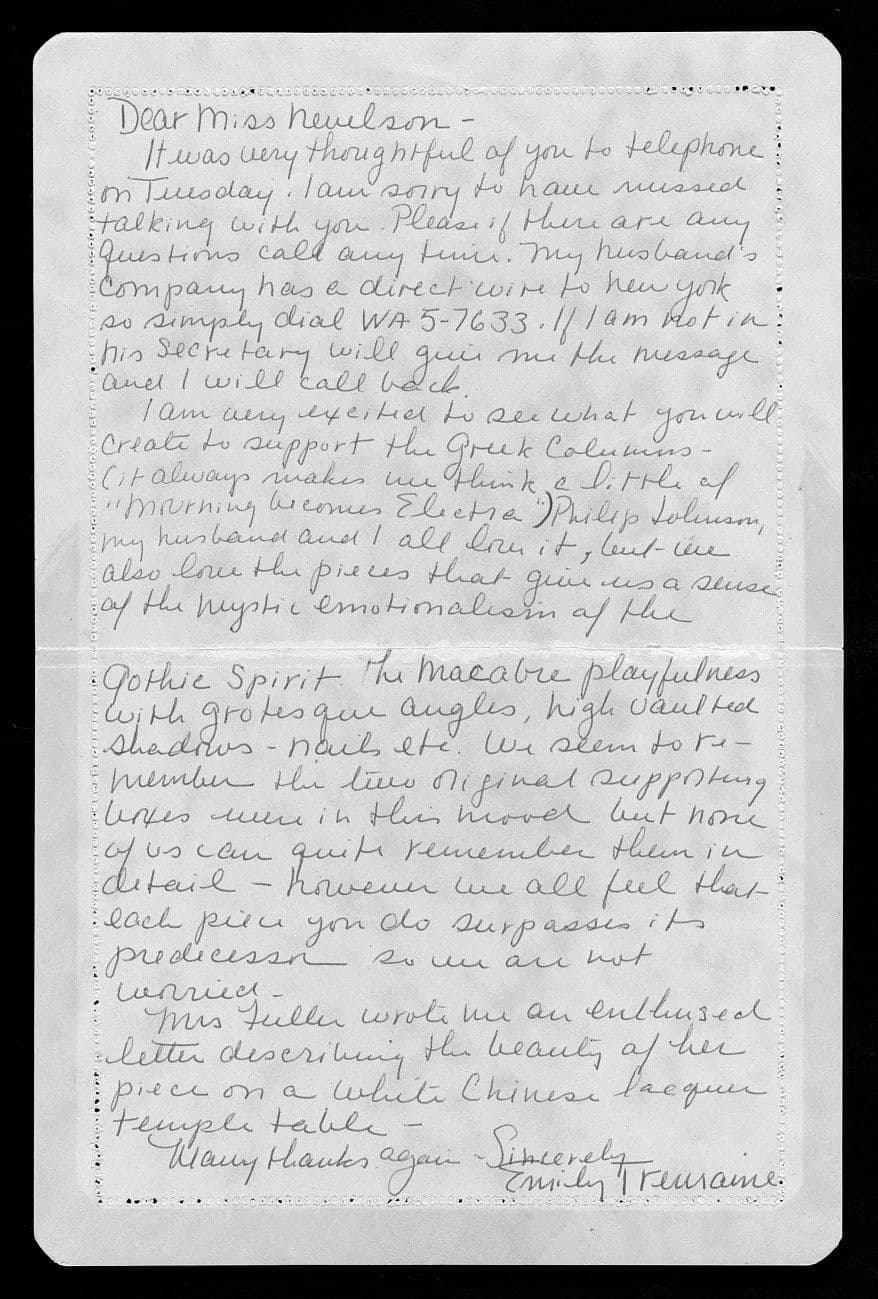

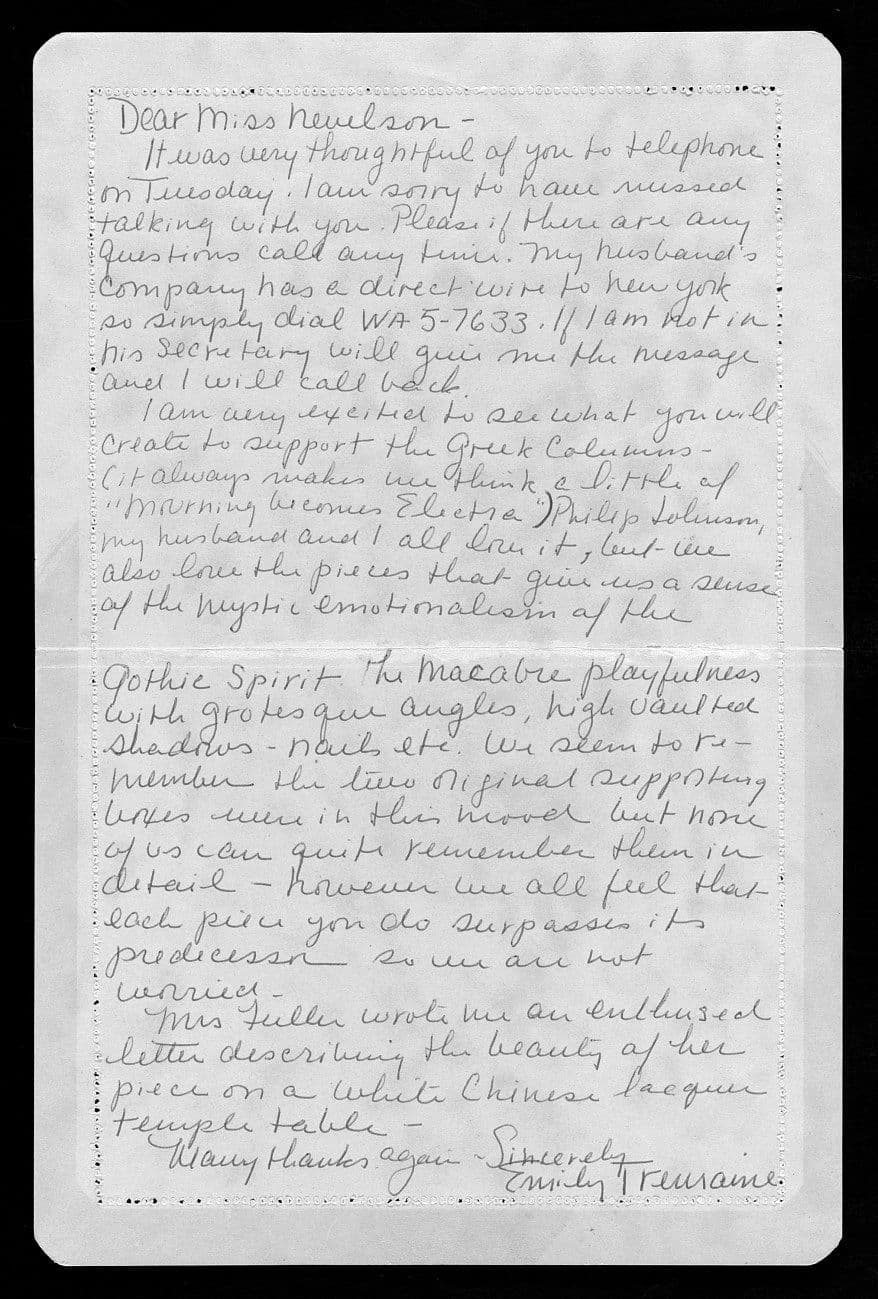

Shaped by Emily Hall Tremaine’s Influence

In Memory of Agnes Gund

The following interview with Agnes Gund was conducted by Kathleen Housley via Zoom on January 29, 2025. Eight months later on September 18, 2025, Gund died at the age of 87, making this interview one of her last. Without doubt, Emily Hall Tremaine and Agnes Gund were close friends. Initially, Tremaine was Gund’s mentor, helping her learn about art collecting, getting her involved in the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, and taking her to visit artist studios to see not just the art but also the act of creation. The first visit was to Mark Rothko’s studio, which made a lasting impression on Gund. From then on, she made an effort to visit studios, getting to know the artists personally. Gund remarked in the interview, “So that was what I liked about Emily, that she really looked at art through a very much wider lens than most people.” As a result, Gund’s own lens widened considerably. During her eleven-year tenure as President of the Museum of Modern Art (1991-2002), Gund helped it expand physically with a greater emphasis on contemporary art. In conclusion, the friendship of Tremaine and Gund went well beyond themselves. It led to a superb legacy for the Museum of Modern Art in particular and the art world in general. The Tremaine Foundation and the members of the Tremaine family are honored to be able to share this interview.

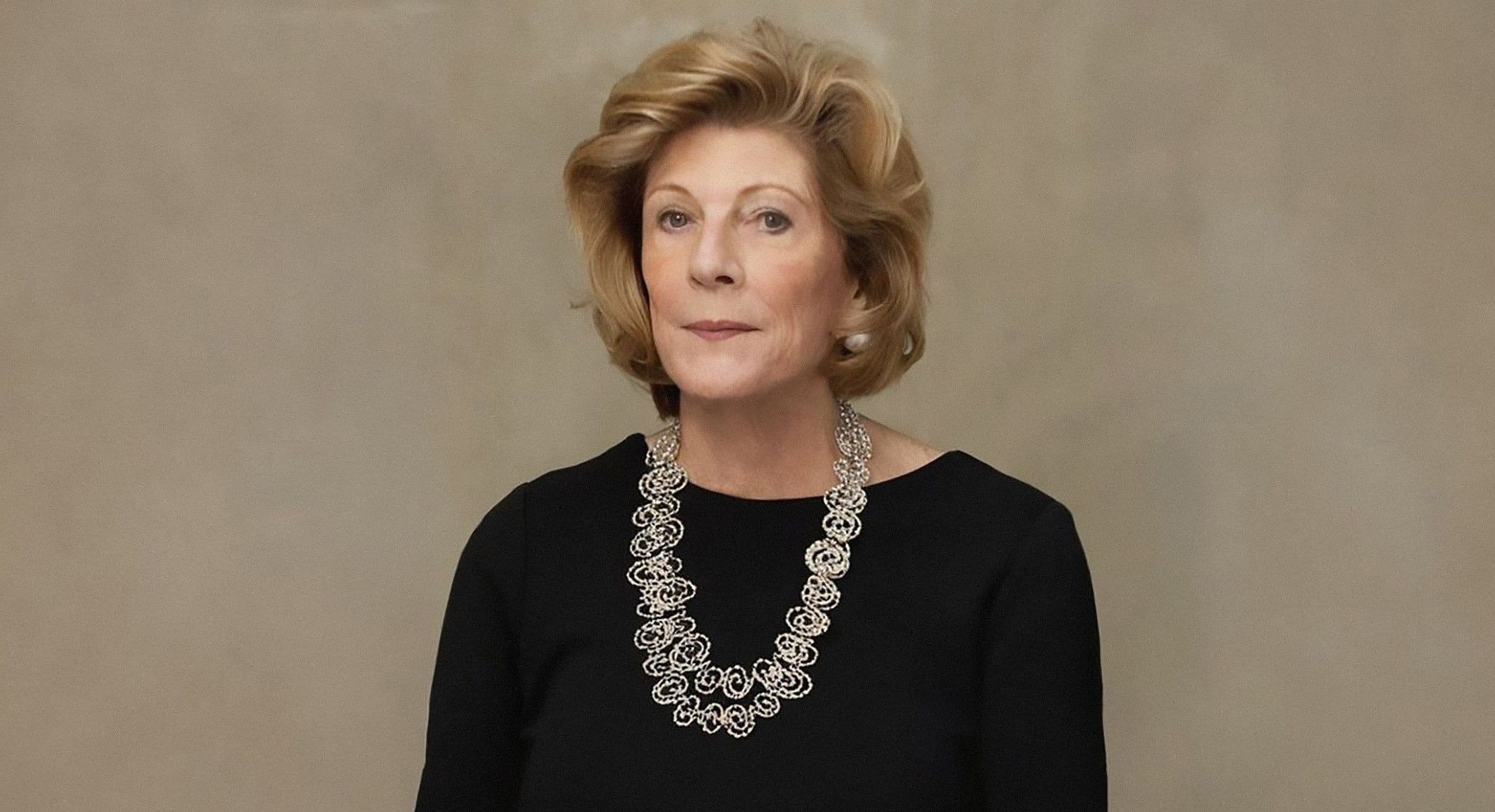

Agnes Gund at the Sotheby's By Women, For Tomorrow’s Women benefit auction held on March 1, 2019, in New York City. This auction was held to benefit Miss Porter's School in Farmington, Connecticut and was co-chaired by Agnes Gund and Oprah Winfrey. Artwork displayed behind Gund is her donation to the auction from Carmen Herrera’s Blanco Y Verde series.

Photography by Julian Cassady / Alive Coverage

Kathleen: I’m just thankful you’re on. And I’m thankful for you giving us your time. Would it be okay if I call you Aggie?

Aggie: Yeah, that would be great.

Kathleen: Okay. I’m Kathleen Housley, and I’m the one who wrote the biography of Emily Hall Tremaine.

Aggie: Yeah, that’s fabulous.

Family photo of Emily Hall Tremaine

Kathleen: Thank you. Well, I just want to start, Aggie, by saying that of course, Emily knew everyone in the art world, but you had a special place for her. And one of the reasons is that I think she saw in you what she saw in herself, which was a very high visual sense, which was innate. And both of you were willing to put in the enormous amount of time and study to bring that to the level that you both reached. Philip Johnson used to say about Emily that she had eyes like gimlets, and he was very jealous of that in her. And I think she saw that in you.

Aggie: Oh, thank you. That’s very nice of you to say, even if it isn’t true. [chuckle]

Kathleen: Well, I think it is true. I’m not saying it just to make you feel good. She really had that ability, and she saw that potential because you were young when you first met her, but she saw that potential in you, and, of course, you fulfilled.

Aggie: It was very helpful for me.

Kathleen: May I ask you some questions now?

Aggie: Yes, sure.

Kathleen: Okay. In the first question I had sent you, I said you visited the Tremaines’s apartment for the first time in 1968. Do you remember how that visit came about? And did you know the Tremaines at all? Burton was from Cleveland.

Aggie: Well, he was on the board of the Cleveland Trust Company, which was my father’s bank. And so I knew him from that, knew him just vaguely, because I was a child then and he was a grown-up. And so we weren’t intimate friends, but we were friends. I mean, I knew of him and about him. But when I met him, I didn’t know that much about him or Emily, but I quickly learned who she was because I was beginning to collect after my father died. I mostly didn’t start until after he died in 66, but then I started collecting. And I knew about Emily from the fame she had, and she was just great. And I really wanted to get things for her and do things for her that I wasn’t able to do because the little things that I called it—the small collection that she had in the study of her New York apartment—were very, very remote for me, even though I thought because they were small things that I could get her something that was small, and she would appreciate that. But it was not to be when we knew each other—from then until she died, and I left it and went away. I went to Connecticut or Massachusetts, really.

“But when I met him, I didn’t know that much about him or Emily, but I quickly learned who she was because I was beginning to collect after my father died. I mostly didn’t start until after he died in 66, but then I started collecting. And I knew about Emily from the fame she had, and she was just great.“

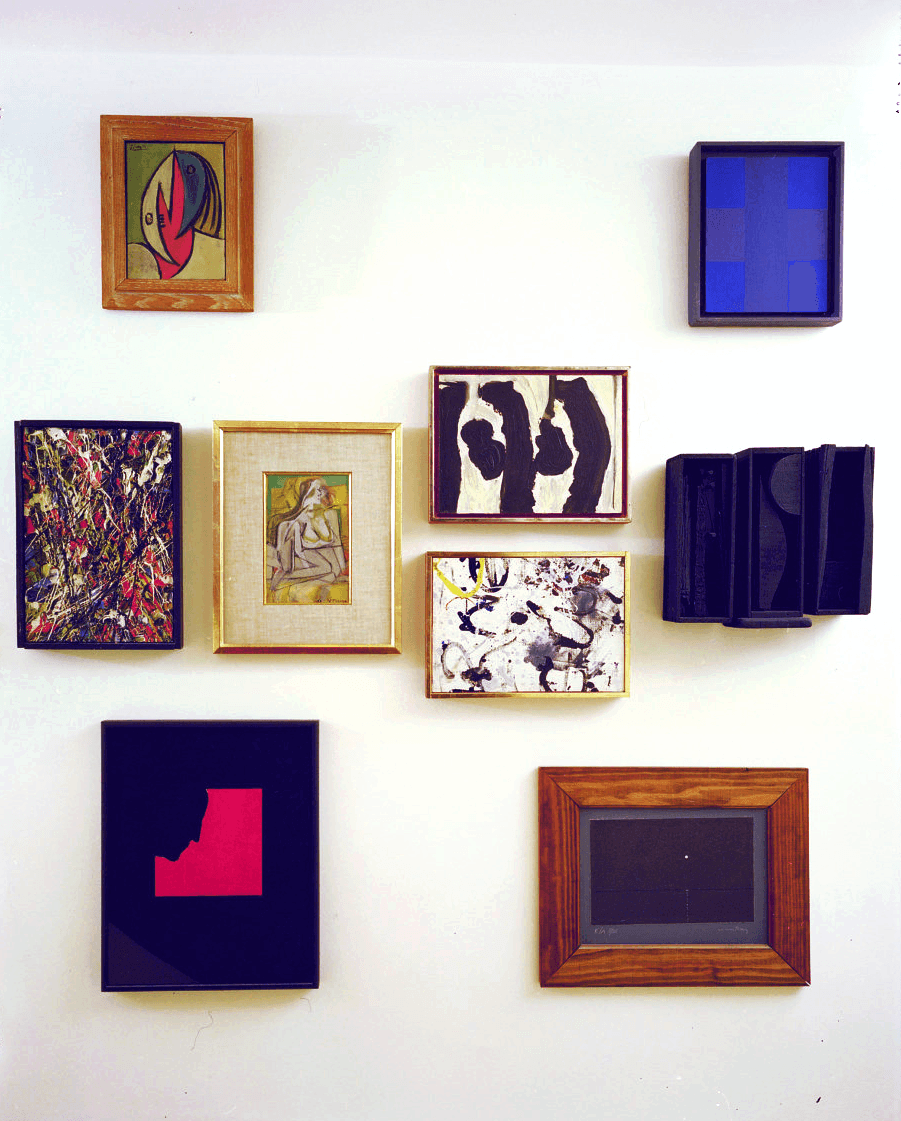

Part of the Tremaines' collections of miniatures on display in their New York City apartment, circa 1984. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Photo: Adam Bartos

Kathleen: You have said that it was Emily who took you to visit artist studios, stressing the importance of seeing what was, she used to say, coming through the artist. What was it like to go to studios with her?

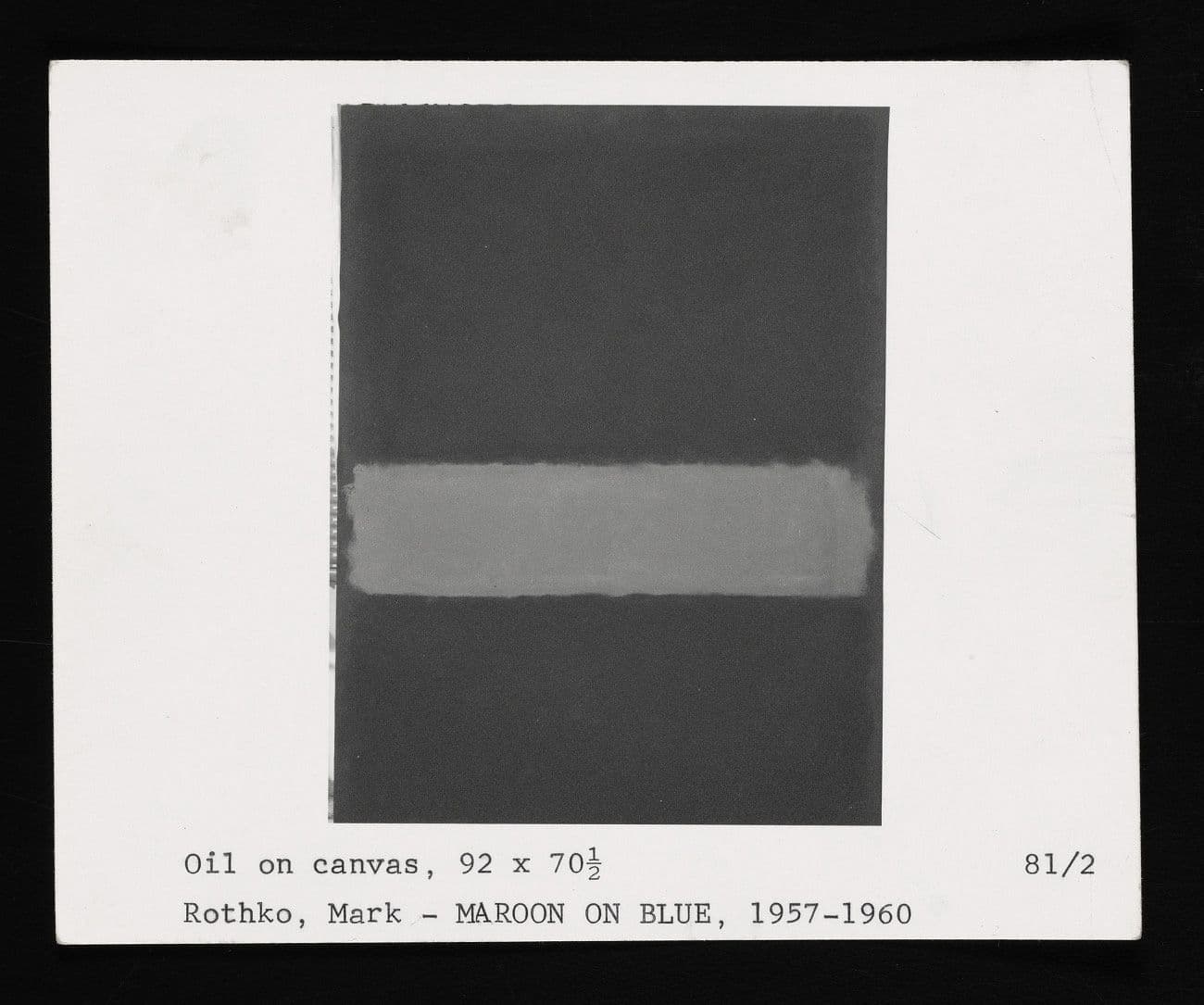

“Well, it was great because she always knew the person, knew the artist, knew the thing we were going to look at. The first thing that I remember most clearly was going to look for Rothko. We went to Rothko’s studio and saw it and it was really a wonderful studio. Then he had gotten—you may remember this—he had gotten a studio that had an opening on the top which he covered and could bring it down and up the way he wanted to, and that’s the way she wanted to see it. And it was he that thought this idea up and it made the light spread over what he showed you or what was up on the wall, which was then all the paintings for the Rothko Chapel.”

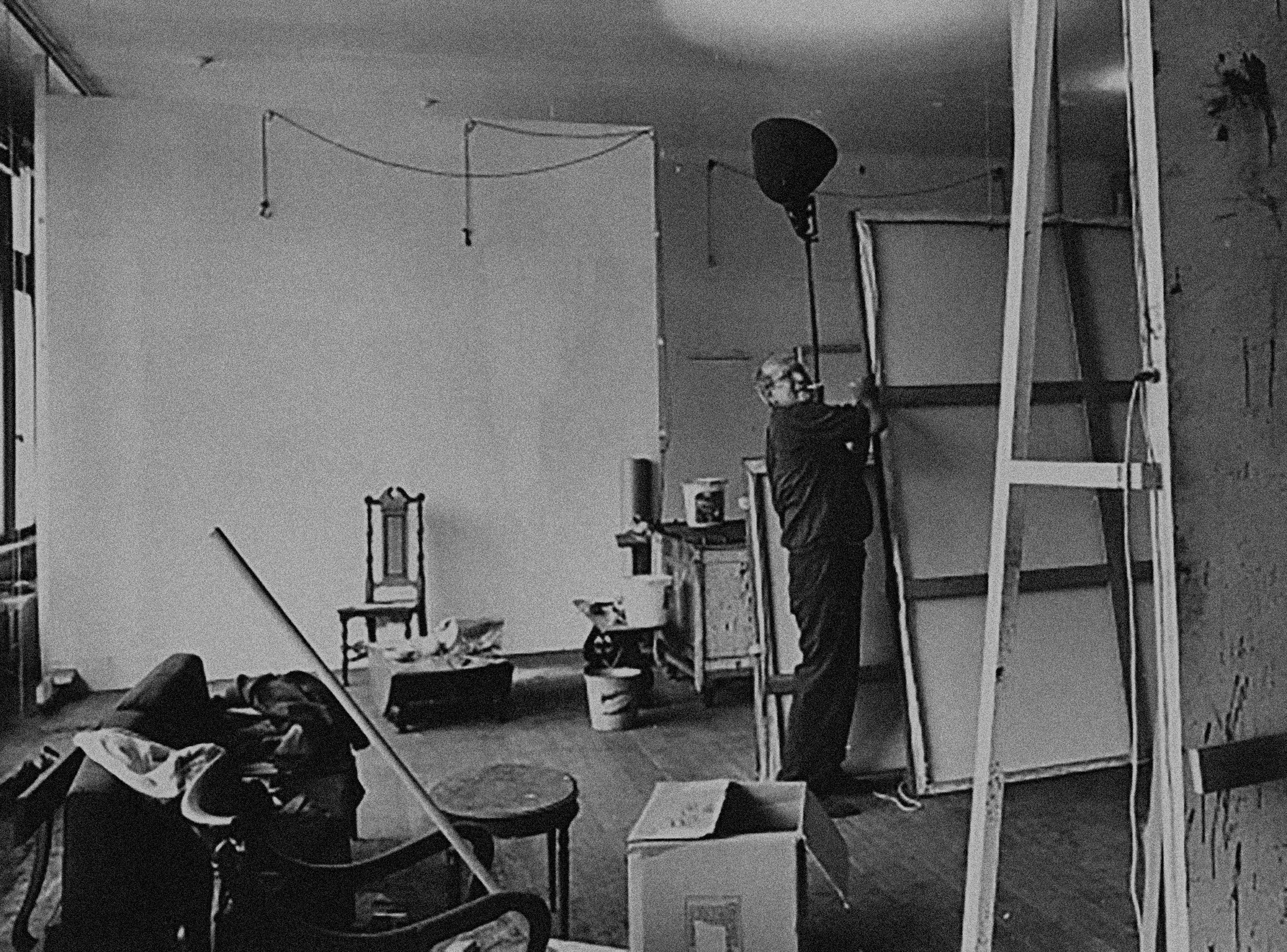

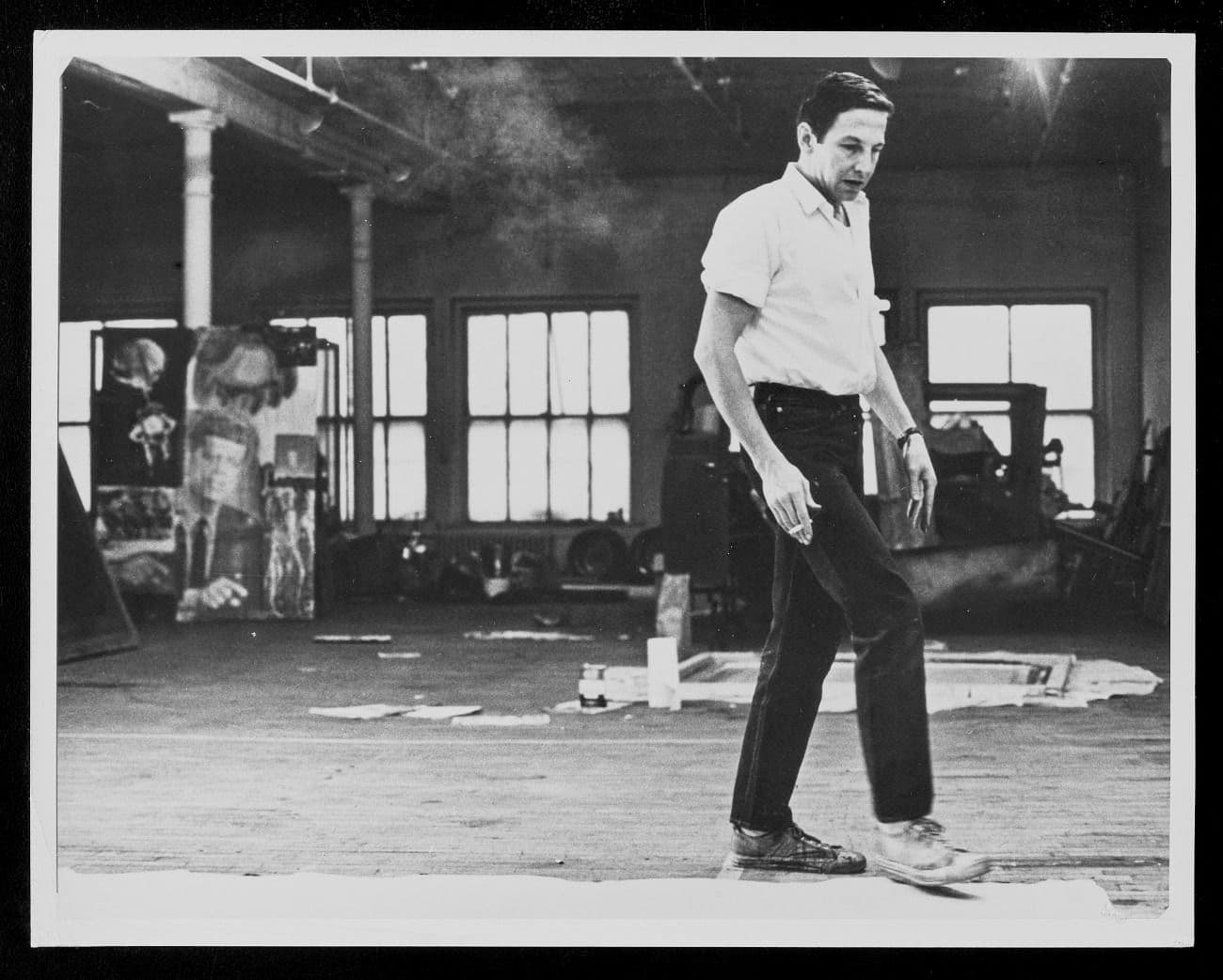

Mark Rothko in his studio. © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography

Mark Rothko, Number 8, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, © 1988 Christie’s Images Limited, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

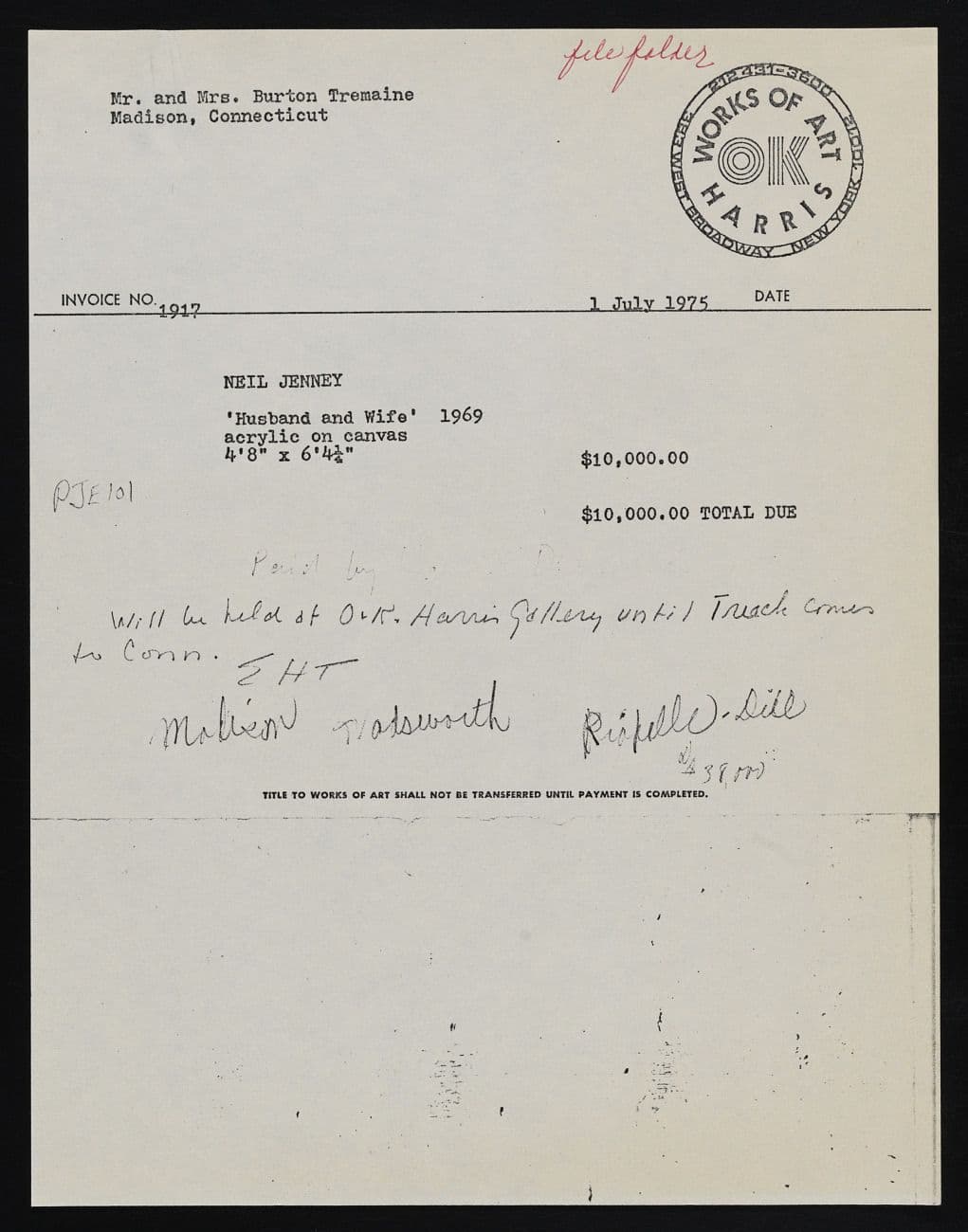

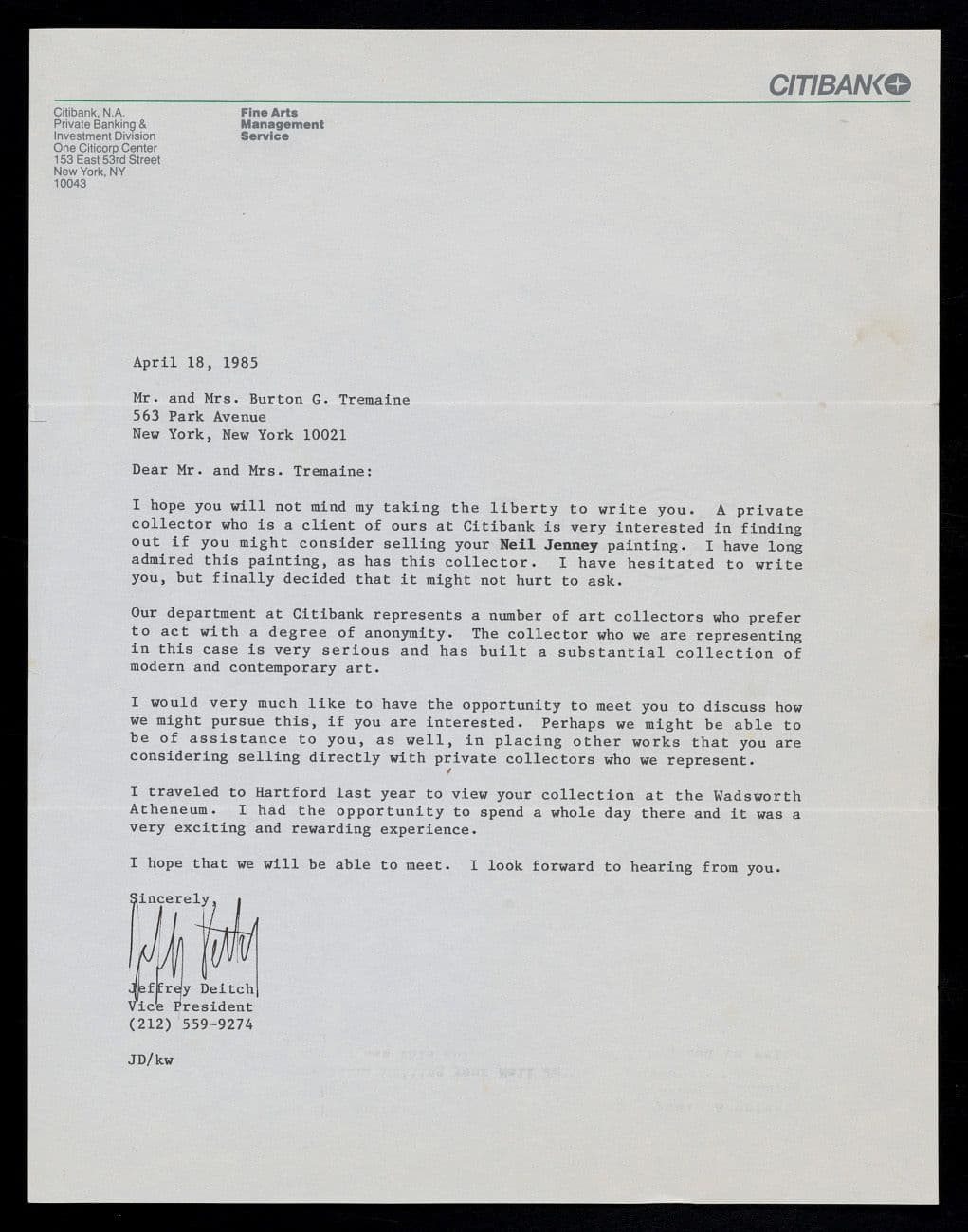

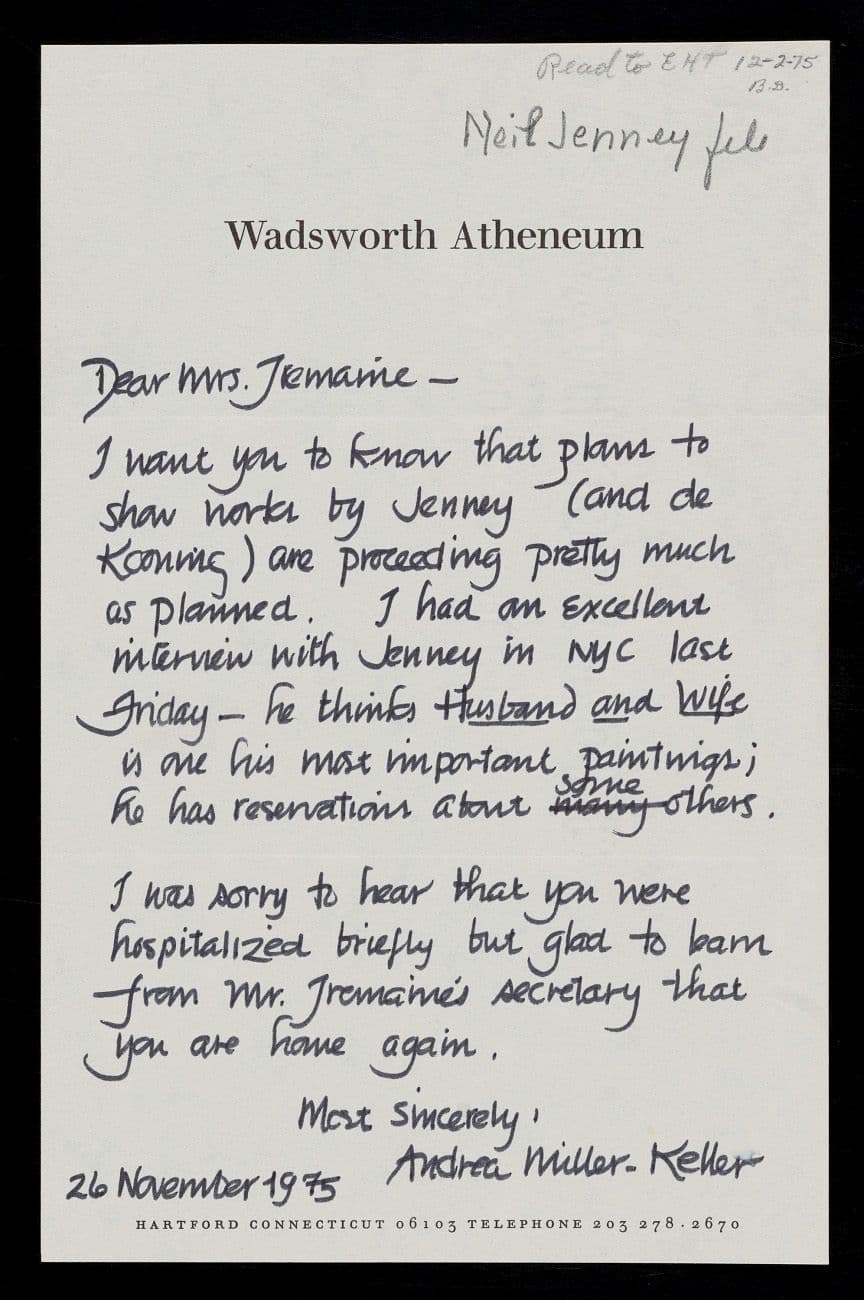

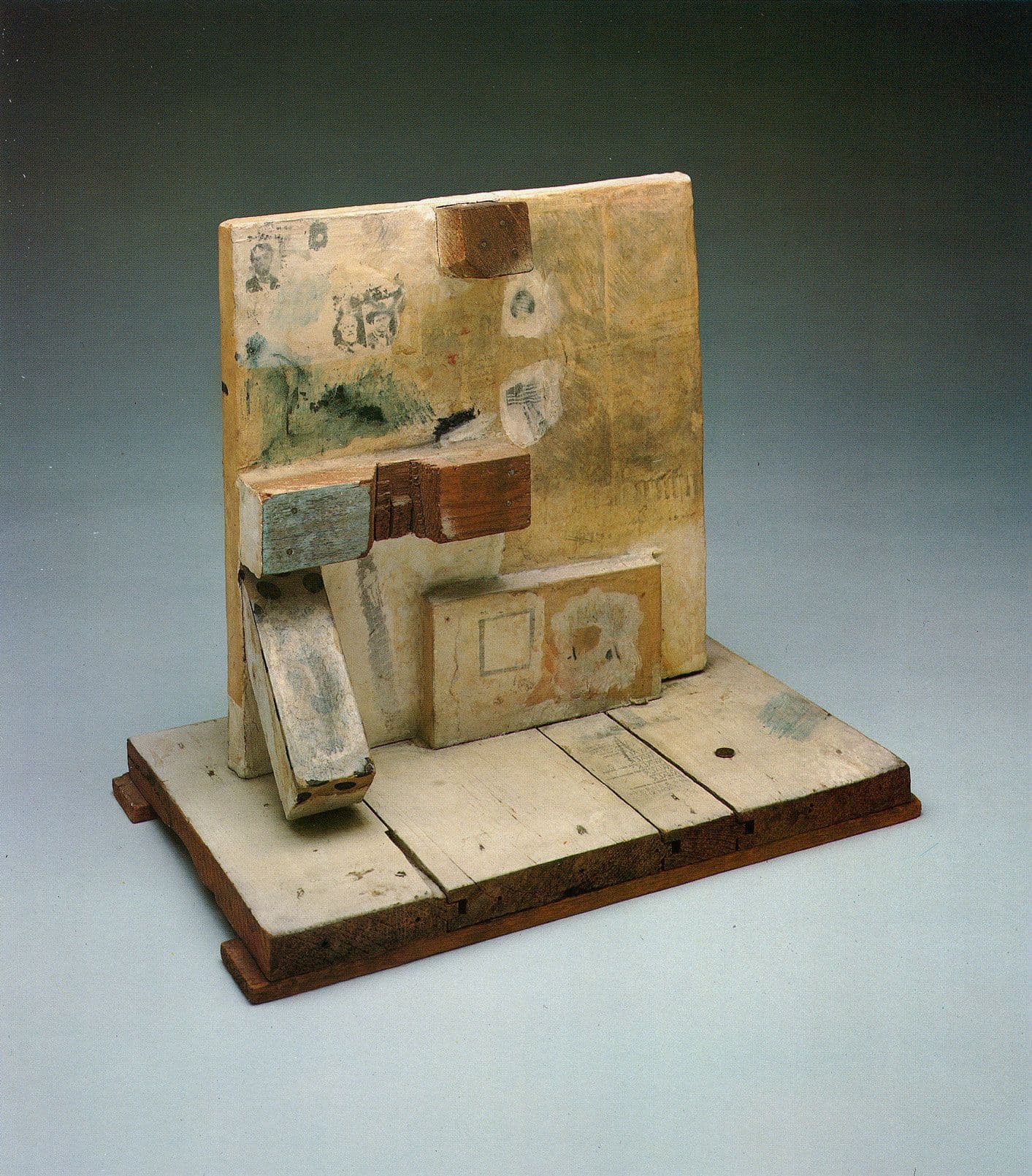

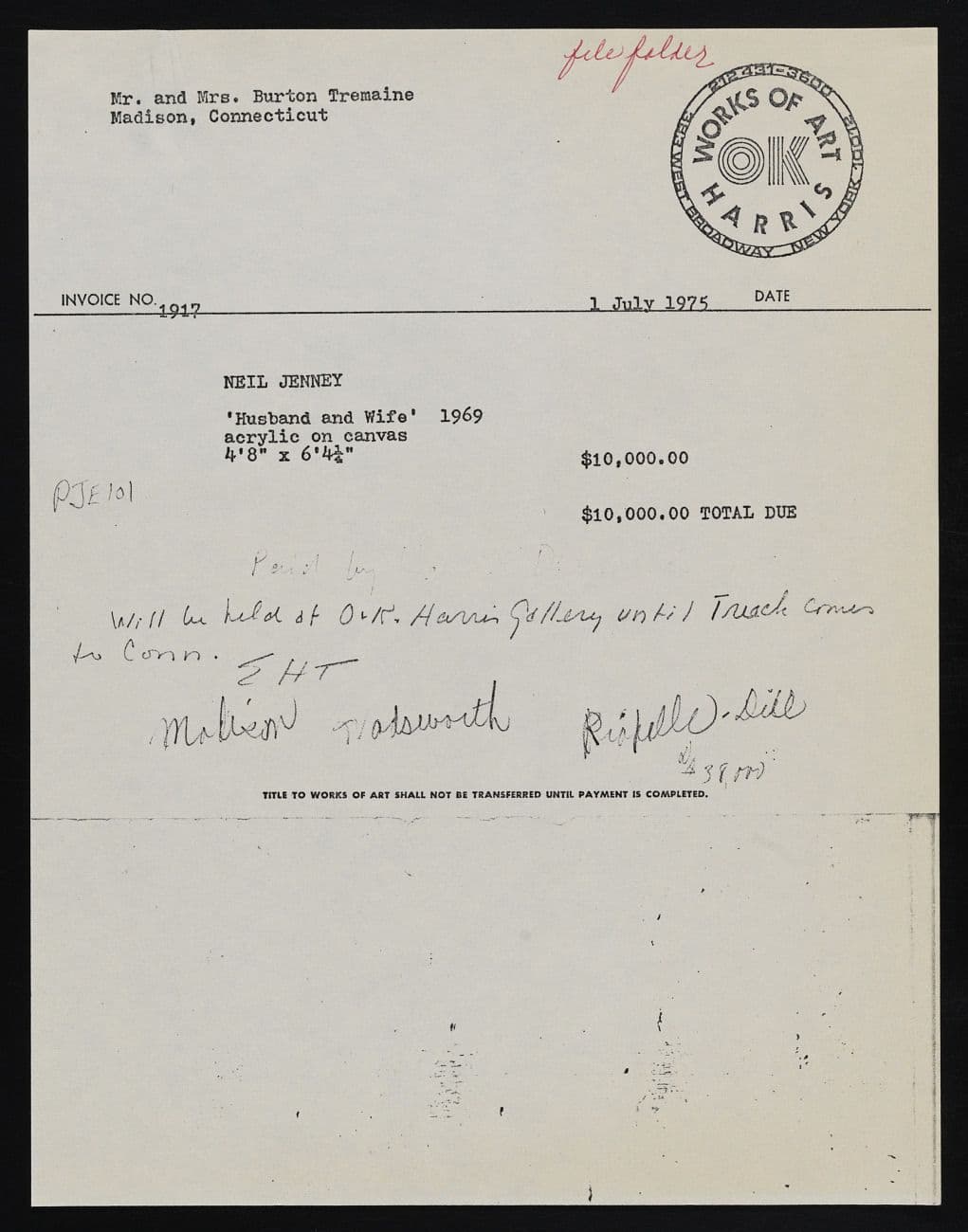

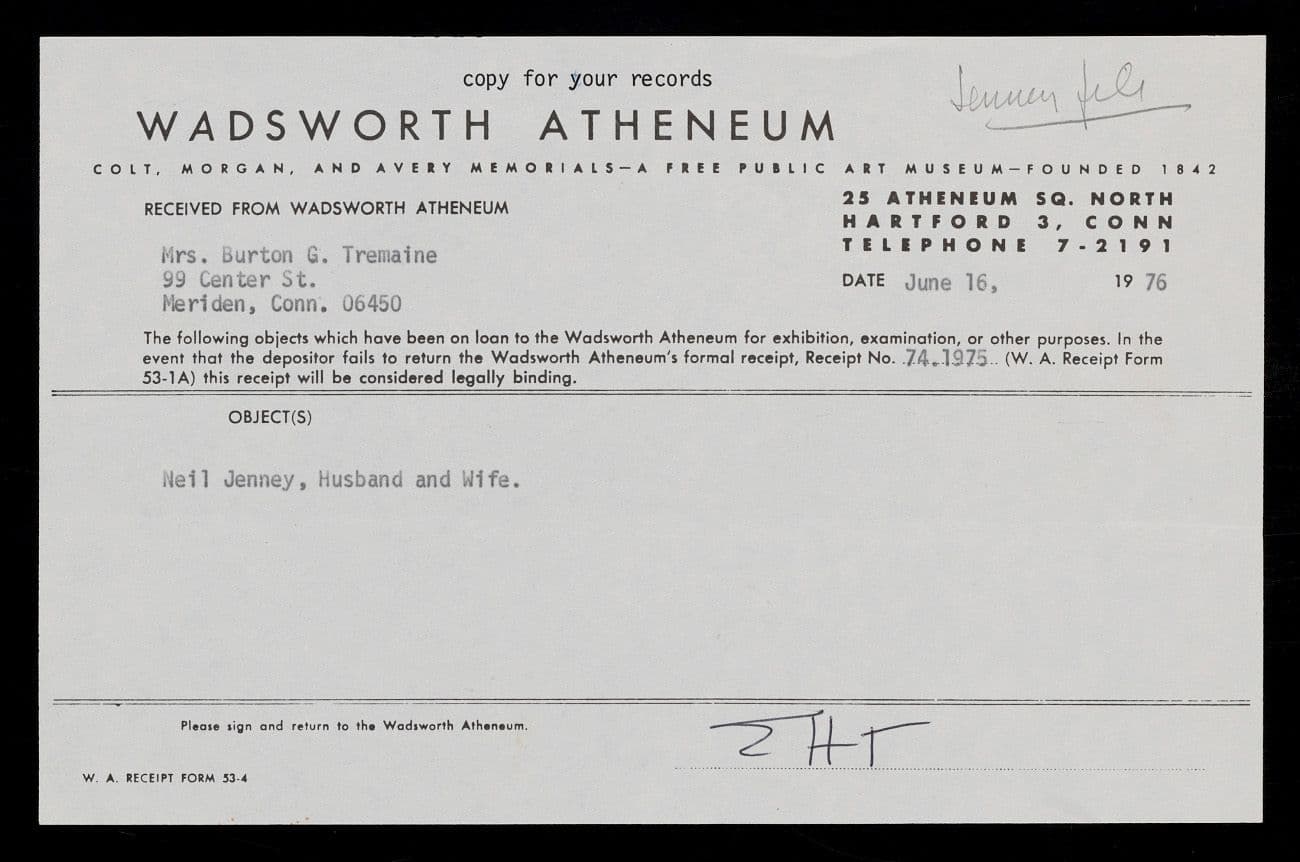

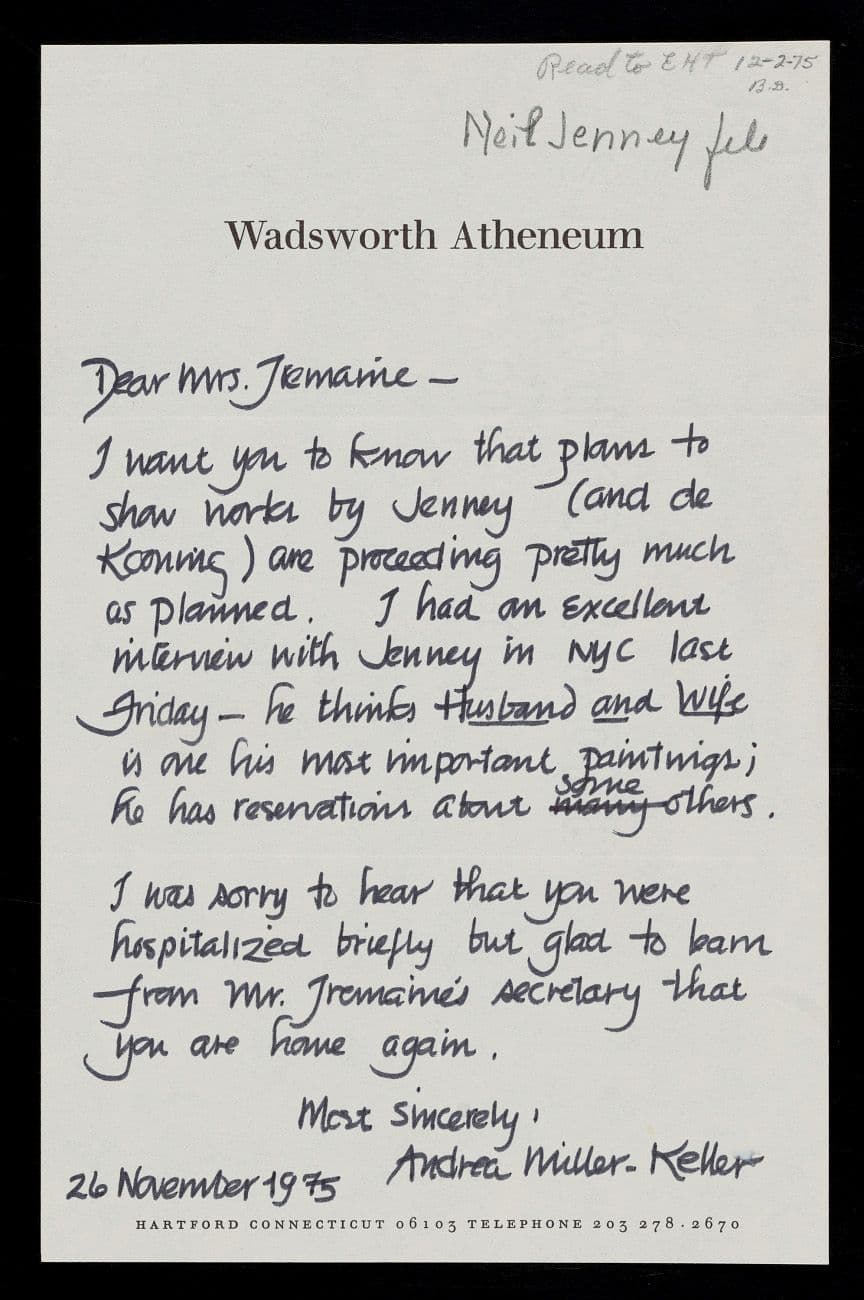

Aggie: Well, it was great because she always knew the person, knew the artist, knew the thing we were going to look at. The first thing that I remember most clearly was going to look for Rothko. We went to Rothko’s studio and saw it and it was really a wonderful studio. Then he had gotten—you may remember this—he had gotten a studio that had an opening on the top which he covered and could bring it down and up the way he wanted to, and that’s the way she wanted to see it. And it was he that thought this idea up and it made the light spread over what he showed you or what was up on the wall, which was then all the paintings for the Rothko Chapel. They were mostly sort of dark brown and brown, different values of brown. But they were really arranged to look very dramatic in that atmosphere. So that was one of the first studios I went with her. Then I went to Neil Jenney’s, who was the person that she liked okay. I mean, she had gotten one of his, or got one at that meeting that we went to see him. And I got the other one, the Dog Chasing the Cat. She got Man and Wife from that visit.

Neil Jenney, Husband and Wife, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, © 1988 Christie’s Images Limited

Neil Jenney, Cat and Dog. Photo: Rob McKeever, Courtesy Gagosian

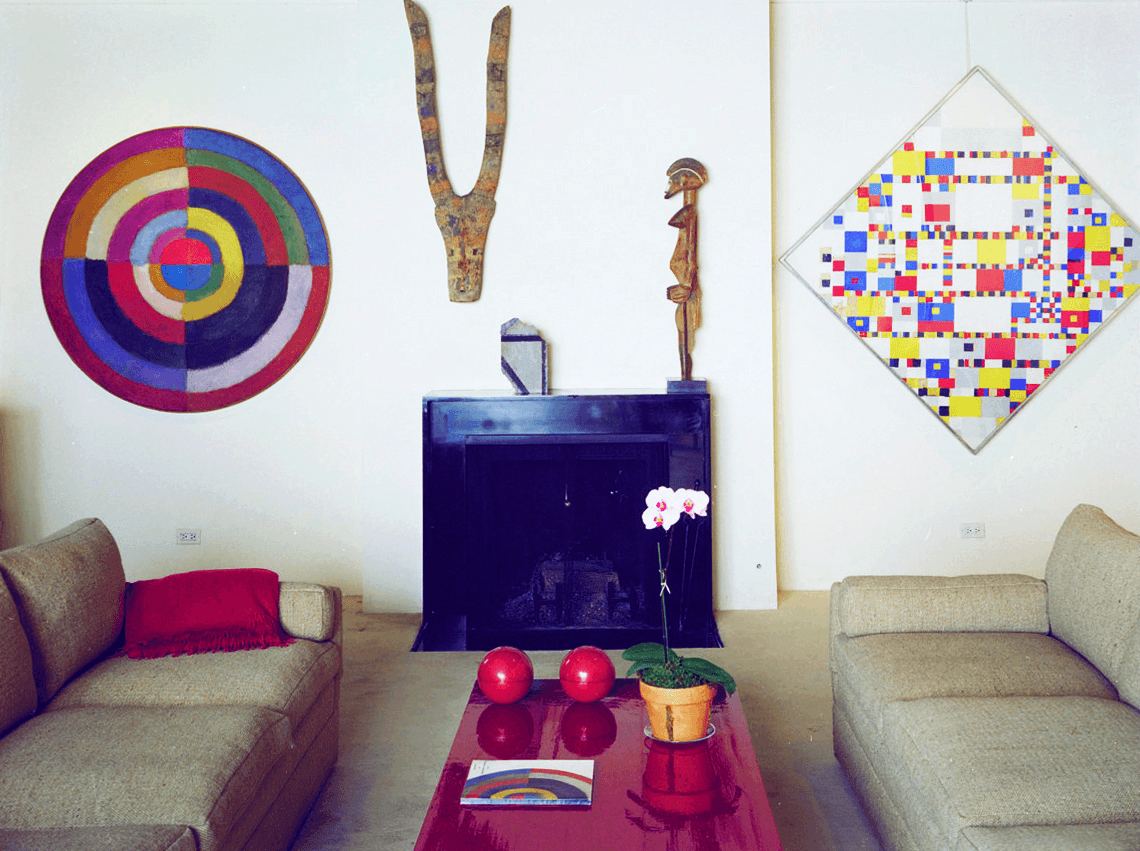

Aggie: And then, I don't remember the others I went to. But the thing that I enjoyed most was going to her house and seeing—their house rather—and seeing what they had, and what they had knocked-down-and-dragged out. I found, I mean, the collection. And it was really—it was very beautiful. They had on one wall over there the Broadway [Victory] Boogie Woogieand the Delauney. But beside it, on the other side was the fireplace—and that was when people used to have fires in their fireplace. [chuckle] Now we suddenly stopped doing that because it really, you know, if anything escaped, and it wasn't good for the paintings.

Le Premier Disque by Robert Delaunay on the left and Victory Boogie-Woogie by Piet Mondrian on the right in the Tremaines’ home, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Kathleen: What was your reaction when you saw the Victory Boogie Woogienext to the Delauney? What was it like to see that kind of presentation?

Aggie: Well, it was just mind blowing because I thought it was very beautiful. So, I really was interested in that and how they looked. And she had the Trova that was in the middle of the room, and it was—I hadn’t really, to that point, been very interested in or looked at sculpture, so I was very interested in that piece when it was there. But she replaced it with something. I can’t remember what that was.

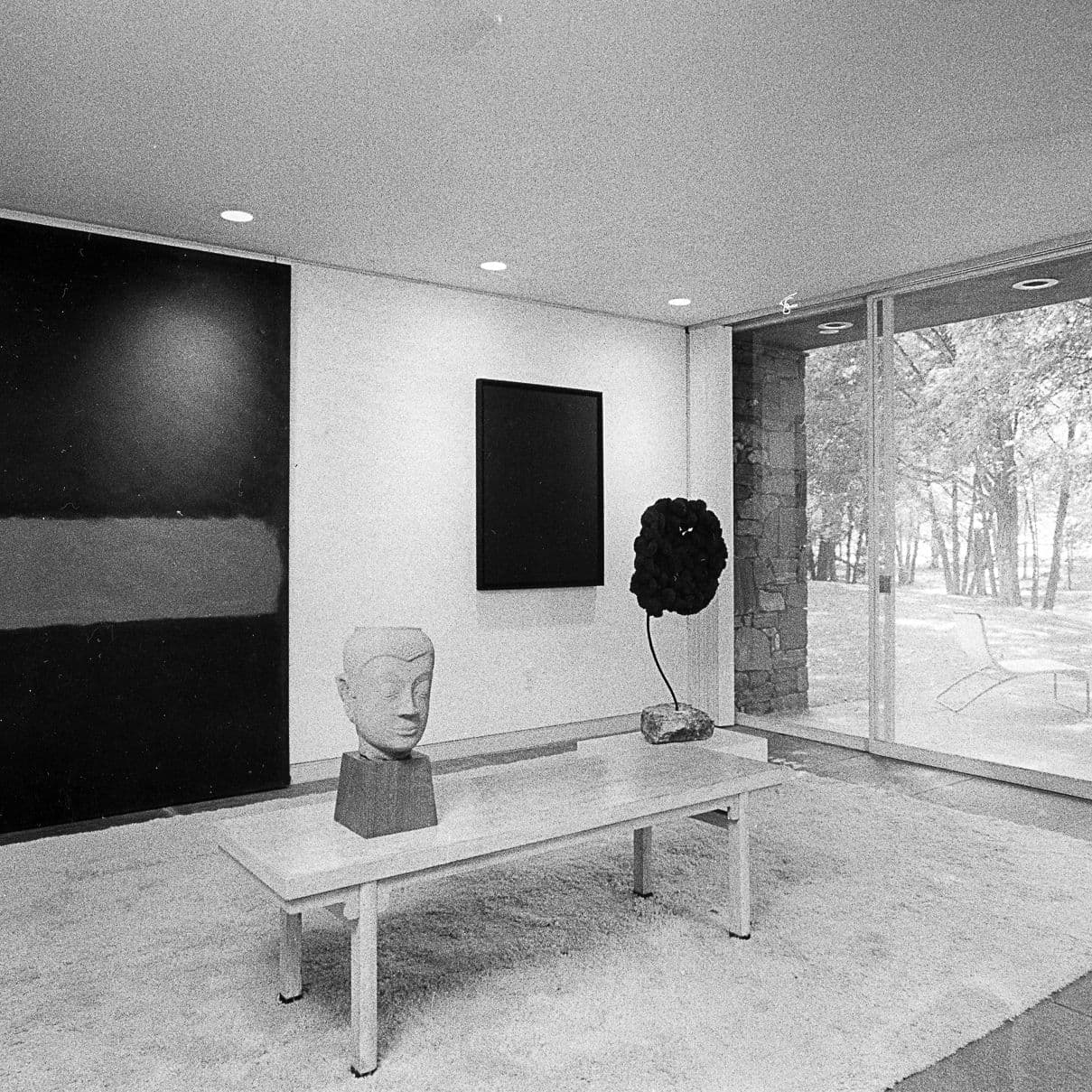

The New York living room of Burton G. and Emily Hall Tremaine. Featured: Falling Man Series: Carman by Ernest Trova. Victory Boogie Woogie by Piet Mondrian on wall at far left, sculpture on left Bougainvillea (1945) by Alexander Calder, Number 8, (1952) by Mark Rothko on center wall, Ceramic Head with Blue Shadow (1966) sculpture by Roy Lichtenstein on table, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: William Grigsby, Vogue, ©Condé Nast, Image Syndication.

Kathleen: So you really bring up the topic of how to live with art. Not just how to collect it, but how to live with it each day, which she really felt was a critically important part of her life. You didn’t just select and stick up. You were talking about the Rothko that you had purchased. And on this subject, how has your perception changed over the years because you’ve lived with a work of art?

“Well, I lived with it and I moved it. I moved it to be beside the window in the dining room, which was completely different from where it is in the living room. It gets no light in the living room, and in the dining room, it had this full light on it, and I thought it was just breathtaking until somebody started saying, “You can't leave the Rothko out in the sunlight. It isn't good for it. And it won't last very long because Harvard was a perfect example of that.” And so I brought it in, and it's been on the wall in the living room ever since."

Agnes Gund in her New York apartment with Mark Rothko’s ‘Two Greens with Red Stripe’ (1964). Beside her is Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s ‘Wrapped Champagne Bottles’ (1965). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Stefan Ruiz, Vogue, ©Condé Nast, Image Syndication

Aggie: Well, I lived with it and I moved it. I moved it to be beside the window in the dining room, which was completely different from where it is in the living room. It gets no light in the living room, and in the dining room, it had this full light on it, and I thought it was just breathtaking until somebody started saying, “You can’t leave the Rothko out in the sunlight. It isn’t good for it. And it won’t last very long because Harvard was a perfect example of that.” And so I brought it in, and it’s been on the wall in the living room ever since. So I brought it before it could get damaged by the sunlight. But I loved it there. It was so beautiful because it had so much depth and really seemed like a painting that would last forever there. It wasn’t a good place for it, and we haven’t loaned it ever since. Even with the machinations about the Rothko holdings or anybody’s Rothko holdings, this was not a place for that painting. And I should have known that right away and not tried to experiment with it, which was... Who did the painting behind you?

Kathleen: Oh. [chuckle] A grandson, Aggie, which you would appreciate. I have grandchildren art in my own office.

Aggie: Oh, that’s great.

Kathleen: Yes. Yes. And I’ve seen photos of your grandchildren, and I know you are close to them as well, so it’s lovely. Thank you for asking. He’s a child who just adores art, so [chuckle] it’s great.

Aggie: That’s fascinating. What is he doing now?

Kathleen: Well, he’s all of 10 years old, so it’s still moving along.

Aggie: Okay. That’s good. But you don’t know whether he will turn into an art appreciator or not.

Kathleen: Well, at least an art appreciator. Whether he becomes an artist or not is another matter of his own making and his own choosing.

Aggie: Yeah. Well, that's good. That's great.

Kathleen: Let me ask you. Emily was a member early on of the International Council at MoMA. Did she encourage you to get involved in the Council?

Aggie: Well, she often would say something about the person from Seattle. I forget her name now, but she was a very well-known collector of art and she would [Emily] encourage me to talk to her and to talk to the people that were on the council. She really learned the names of the people, everyone she met she knew after a while. And she was one of the people that I sort of glommed on to and got to know. Emily was a wonderful person and she told me to listen to those people, which I unfortunately haven’t always done, which was more bad for me than good, that I didn’t take her word for it at that time, because they’ve always been people who knew a lot and who were very interesting to know.

Kathleen: Did you ever go on any of the International Council trips?

Aggie: I used to go on them a lot when I was younger, and I really loved them. They were wonderful trips.

Kathleen: What did they make possible or open up for you?

Aggie: Well, they just wanted to travel. It was quite rigorous because you got up very early and you didn’t get to bed till after dinner. That usually was with one of the people that lived in the city we were visiting or was from that city along with all the other people on the council.

Burton G. Tremaine and Emily Hall Tremaine at their Madison, Connecticut house. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Sculpture pictured at left is Water Ballet by Mary Callery. Sculpture in background is Salem #7 by Antoni Milkowski. Sculpture at right is Falling Man Series: Wheelman by Ernest Trova.

Aggie: Well, I did go on quite a few of them at that time. And the one I remember especially was going to Prince Franz’ house in Germany, in Bavaria where he lived, and he was then head of the council, and he knew Emily, of course. And he was very, very knowledgeable about all kinds of art. And he had a friend that he knew and lived with that was—he was in a relationship with a man. And he was afraid to really bring that out in front of the council. So, but I really didn’t mind that someone would do that. And I think I understood it, even though I didn’t have anybody that I knew intimately that was gay. But it was very true of him, and he was always protecting that aspect of his life.

Kathleen: In the wonderful documentary that your daughter made of you, Aggie, there’s a scene in which you reminisce with Dorothy Lichtenstein about a party given by the Tremaines in their New York apartment with the silver balloons, you know, Andy Warhol’s. Could you talk about that a little?

Aggie: Well, I reminisced with her about the fact that she wore this short, short skirt, and she said she still had the skirt. This was years later when I talked to her about this party that Emily had had and it was her meeting Dorothy for the first time. Because we have a new dog that we just named Dottie after her, after Dorothy Lichtenstein, and because she died just before Christmas—so I think about Dorothy almost every day. But Emily had this party, and she had all kinds of young people, which Dorothy was at that time, at least to me, she seemed to be way younger than I was, but wasn’t at all, because she was—when she died, she was 85, I think, so she was only a year younger than I was. But the party was just full of people that were young, and it had dealers as well as collectors and artists, and it was just a wonderful mix of those things. Emily was really a wonderful party giver. She had lots of people. And I remember saying to her, “Well, Emily, I can’t come because I don’t have a male escort.” And she one time blurted out, when I said that, about three times, she said, “Well, we’re not having sex.” [laughter] And so, she was a little astounded that I thought I needed somebody to come with.

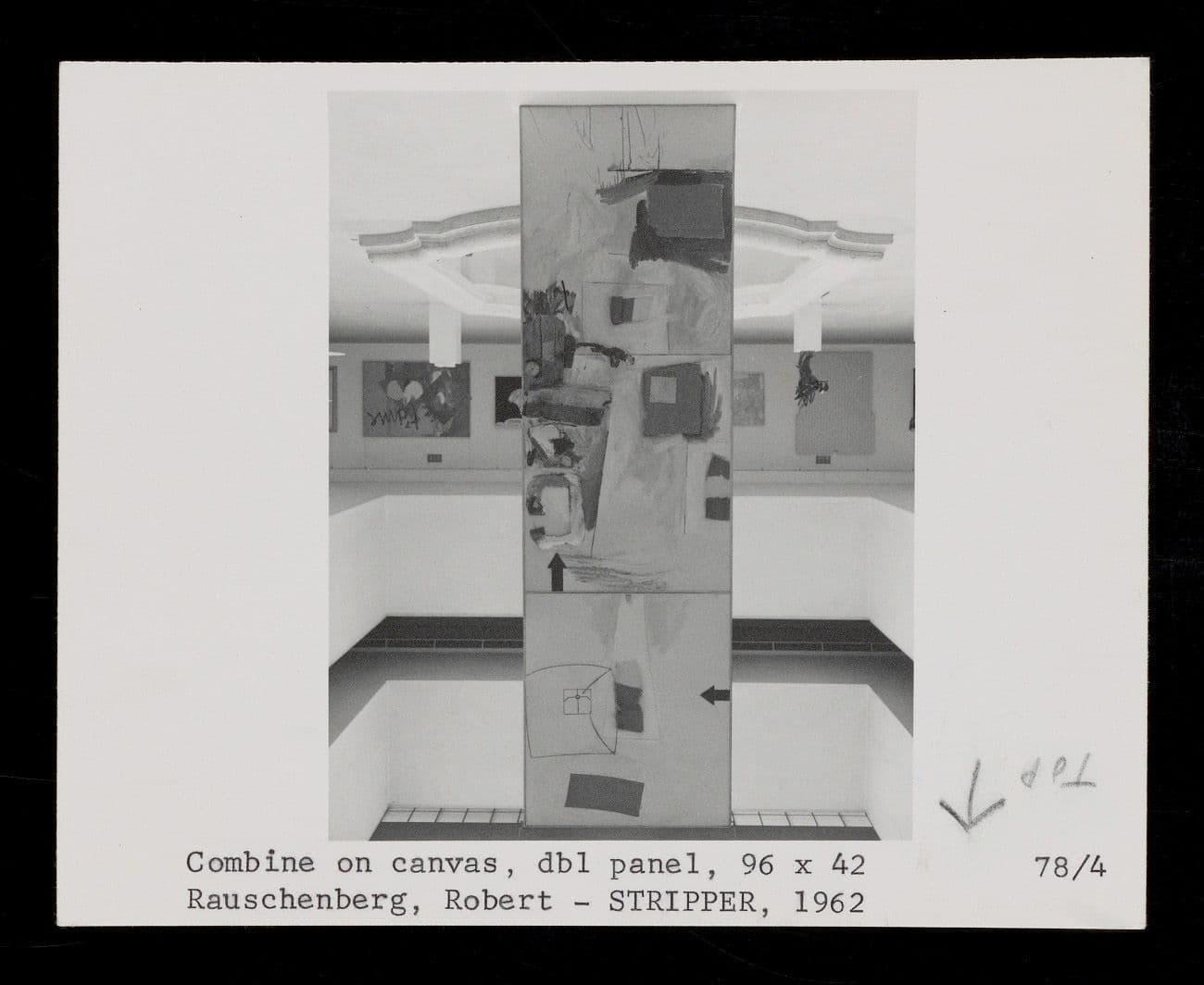

Kathleen: Let me just read this question to you because it’s an important one, and it relates to the party that we were just talking about. Emily often made connections between artists and the art world. For example, Jasper Johns remembers going to a party at the Tremaines at which Harry Abrams and Bob Rauschenberg were in attendance. Emily introduced Abrams to Rauschenberg. As a result, Abrams published Dante’s Infernal. And Jasper said, “I had the idea that Emily had arranged this encounter deliberately to accomplish this.” Just an interesting comment from Jasper Johns. Did you see other examples of where she seemed really to be trying to make connections, particularly between artists and collectors?

L–R: Riva Castleman, Calvin Tomkins, Judith Goldman, Toiny Castelli, Barbara Rose, Jasper Johns, Tanya Grossman, Robert Rauschenberg, Buckminster Fuller, Bill Goldstone, Leo Castelli, James Rosenquist, Ed Schlossberg, 1980. Photo: Hans Namuth; Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Aggie: Well, I did see that with when we went to visit Neil Jenney. Neil is quite an oddball in the art world. He really was at that point very much of an oddball. And she had me come meet him and he very much was a loner. He kept to his art part and I don’t know, I never really did understand him and still don’t. But I ended up buying the piece of the Dog Chasing the Cat, which is a very big and long piece and we’ve had it in our house. Now, we have it up at the farm and it’s a really wonderful piece. But we did get a later work by him, North America, and we really like that. We have enjoyed it and still have it, but haven’t done anything with it because we don’t have it in the house now. We took the other one up to the country and it’s really lived very well up there.

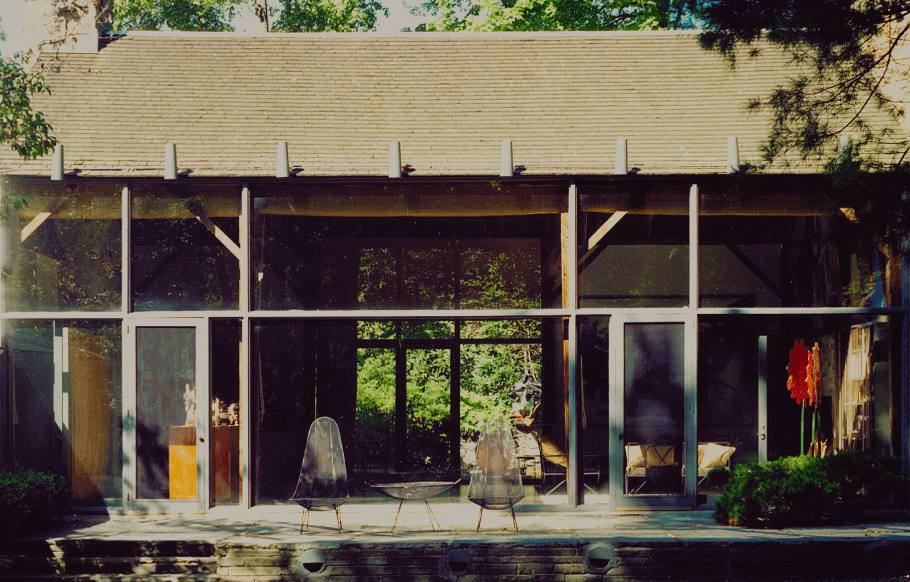

The barn at the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Kathleen: Did you go to their place in Madison?

Aggie: Yes, I did.

Kathleen: Remember the barn that Philip Johnson redesigned?

Aggie: I did remember the barn.

Kathleen: What was it like to see all the art and the barn and then also their sculpture garden? So, it was kind of an in and out quality, an interior/exterior quality, to how they were showing their art there. Do you remember?

Aggie: Yeah. That, I do remember, that was a good part of it. And I remember that the pool that they made, around which this art lived, was kind of a wonderful pool that overflowed and it was Philip Johnson that designed that pool, and I remember being interested in that. But it was very nice to be with them up there because that was the last time I went up there. And so, I didn’t go often but we also met one time with the Tremaines in one of the International Council members trips in which we were going down the Thames in a boat with artists. And I remember coming in, I came in a little before they did and I went in to be introduced and I remember somebody was standing by the photographer and when I came in they shook their head, no, that I wasn’t somebody fit. [laughter]

Aggie: And it was very funny. It didn’t bother me as much as I guess it should have. But I passed it over and we went on down to celebrate in this place that was sort of Mead Hall, a big dark room with all these artists and everything that came along with us and people that were well known. But I never forgot that one name of the photographer person that was by him. I didn’t know who he was at the time.

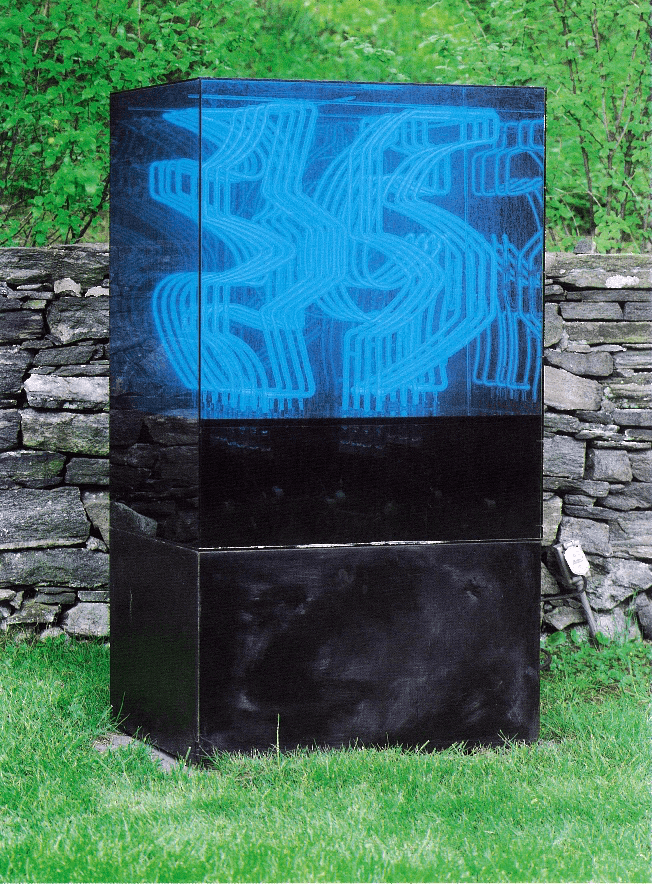

Fragment for the Gates to Times Square by Chryssa, part of the Tremaines' sculpture garden at their home in Madison, CT. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

Pool at the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut.

Background image: Pool at the Tremaine home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. Foreground image: Human Lunar Spectral by Jean Arp. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Kathleen: Yeah. In regard to their home in Madison, the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation has purchased that property, which had left the family. They’ve repurchased it and they’re now studying how best to use that property, whether for education or exhibitions. All possibilities are being examined. Do you have any thoughts about how that beautiful property could be used for the betterment of the art world?

Aggie: Well, I do. I think it would be wonderful for a residency. I mean, if they had a residency program like the Rauschenberg Foundation has in Florida or Captiva. They have a wonderful place that one of my nephews, he’s a nephew by marriage, has been to. And it’s just a wonderful place, he says, and works very well and it’s kept on working. And I think a residence would be good because you could limit the people or increase the people, whatever you wanted to do, that came, and they would stay for a certain time. You could make what they had to do either limited or make it very rigid. You could do anything you want with the residency. Elizabeth Murray has a residency, and I know many people have them, and I think they’re really very good. You have to know what you’re doing when you have one so that you do it right. Because you can end up spending all kinds of money on something that doesn’t have any, you know, later aspect to it. But mostly their residences are very good things. I think she [The Tremaine Foundation] could do that because she has enough rooms in the house. How many rooms would you need if you had four people as residents at one time, or six or eight? Whatever you need you could have. I forget if there was... Was the barn converted?

Kathleen: Well, you had the barn and then there was a little section that was attached to the barn, which they did use for guests.

Aggie: Yeah.

Kathleen: And then upstairs there were three bedrooms. The house is quite large. But they’re looking at all those aspects and how they can connect things. Your advice, though, is very much appreciated.

Aggie: Yeah. Well, I just think these are very well done and very well run. And we used to go to one in the summer, which I think most everybody went to. It was later, came much later than Emily and Burton lived, but it was in Maine, and it was run by, I think... Let’s see who ran it. Kippy Stroud was the one that made it, and it was just a wonderful place. We had all kinds of husbands of artists or wives of artists that weren’t artists themselves reporting on what they did. And very often that was more interesting than what the artist was saying that he or she did. And I learned a lot from that.

Sculpture by Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, Year of Christie’s sale: 1988, ©1988 Christie’s Images Limited, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the Archives

From the Archives

Kathleen: Let me tie that to a different question, just to broaden it out. And I had picked up that way back in 1991, when you address the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, you said, and it’s a wonderful statement, “We must embed in our fiber as a nation the notice of the arts as a necessity, integral to our strength.”

Aggie: Yeah.

Kathleen: And I think Emily would have agreed with you. It also ties into what you're saying here. Do you have any other thinking about that statement which you made all those years ago about embedding art in the fiber of our nation as a necessity?

Aggie: Yeah. And I think it’s really important now that we have this monster person that is putting out all these things that he’s deciding to do spontaneously, more or less that is Trump, that I don’t think Emily would have agreed with him or wanted him to be controlling all the things he is. But I think it is something that I’ve been interested in doing. And we’re now at kind of a very difficult part of [Studio in a School,] which is what I’ve done with that idea. And I think it doesn’t matter if we don’t get any artists out of it. By bringing art, it always helps in some way. It may not be that they become artists or have any interest in being artists themselves, but it really does embed in them something that is different that they don’t often get at school. And this is why I think it’s so important, because I think it’s, you know, I’d say in a different way than I used to, than I said with that quote that you just read. I think art carries out into so many things.

"By bringing art, it always helps in some way. It may not be that they become artists or have any interest in being artists themselves, but it really does embed in them something that is different that they don't often get at school. And this is why I think it's so important, because I think it's, you know, I'd say in a different way than I used to, than I said with that quote that you just read. I think art carries out into so many things."

Aggie: And one of the reasons I feel so strongly about having it is because I didn’t have any real entry into it myself. And I’ve seen with things as broad as, you know, when I was a troop leader for the Girl Scouts. And they had some child that came up to me and all in tears because her mother had been to the school the day before I met with her. And she was so upset because they’d taken her rabbit that she’d done down because it had five legs instead of four, and was a little bit different than everybody else’s. And they had taken it out of the exhibition because they didn’t think it was right to show something that was not real. That was really why I wanted to start this program, that kids would be able to do things that they saw and that they thought were important as well as the regular things. And so I do think art is very, very essential now and especially for young children when they don’t know anything about somebody famous or well known. We had prints that we had made and we had the person come for a visit to a school. And they were just terrific, wonderful artists like Jeff Koons and Clifford Ross and, you know, just Sarah Z come and on and on, I could go on. But there we’ve had about 25 artists that have come through the program and made people really understand their teaching. The artists are not very famous, although some are. And we’ve had very famous artists come and they [the students] see the difference in all of them and don’t necessarily like one kind of artist over another. Although when Jeff Koons came, all the teachers in the school came to see him. And the room was just packed with people that we don’t usually see in another artist’s place. But so anyway, I like all the programs we have, even if the artist is not well known. And most of these teaching artists stay there quite a while. And we have them that have been there for 35 years, and we’re [Studio in a School] only 40 years old or 40 something.

Kathleen: Right. That kind of ties back into the quote I gave you about seeing what was coming through the artist, that Emily said. It wasn’t just what was on the walls. What fascinated her was the process itself and how an artist actually created in an ongoing way, which is what you’re talking about with the children when you bring in artists like that. I used the word neologist about her because she said that she was always interested in the new. It wasn’t that she didn’t love what had been created already, but this incredibly empowering process, which was art itself, was a fascination to her. And I presume it is for you as well. I mean, that was one of the things again, when she first began to go out with you to the studios and to actually see what was happening in the studios and how the art felt different in the studios.

Aggie: Yeah. Yeah. I think I learned a lot from Emily. Emily was very generous with giving of her time, and she did take me around a lot. We went to other things than art things. We went sometimes to a dance program or a program on an artist that wasn’t well known. And I never found out if they did make their way as an artist. But just going with her and seeing her reaction to what they were doing was very good.

"I think I learned a lot from Emily. Emily was very generous with giving of her time, and she did take me around a lot. We went to other things than art things. We went sometimes to a dance program or a program on an artist that wasn't well known. And I never found out if they did make their way as an artist. But just going with her and seeing her reaction to what they were doing was very good."

Nevelson in her studio, Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Kathleen: Yeah. Did you ever visit Nevelson's house studio with her?

Aggie: No. But she came to one thing that I went to with Emily, I think, and that might have been just another artist's work or something. I did see her, and I remembered the long eyelashes...

Kathleen: Eyelashes. Right.

Aggie: She had, and she always was dressed very much in something unusual and usually attractive. And I remember meeting her, I think I met her through Emily. I'm pretty sure I met her for the first time through Emily, and then...

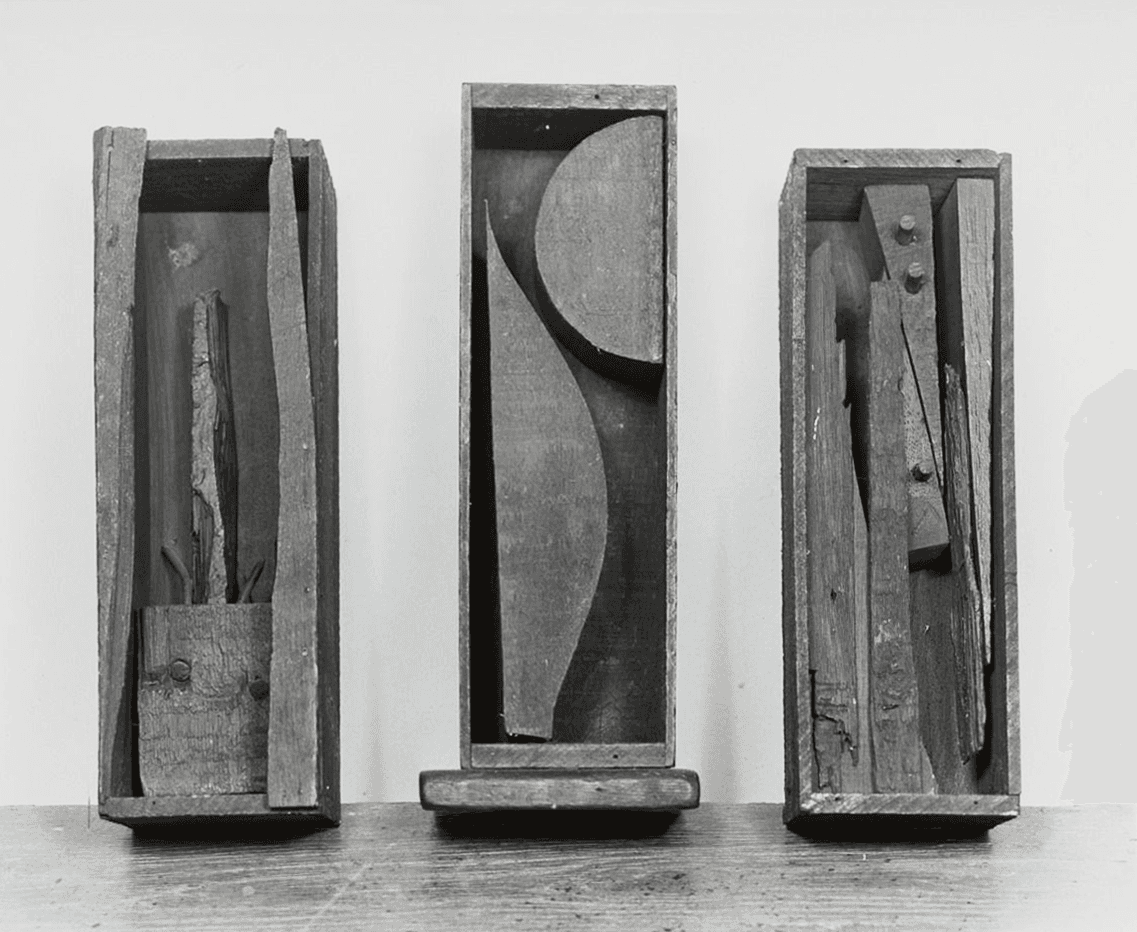

Kathleen: Because she was one of the artists, Emily owned her Moon Garden Series...

Aggie: Yeah.

Louise Nevelson, Moon Garden Series. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kathleen: And was quite taken by what Nevelson was attempting to do in the probably late 1950s into the early ‘60s, I think. So that’s interesting to know that you did meet her.

Aggie: Yeah, I did. And I don’t remember how, but I think it was Emily.

Kathleen: I have only one other question for you, and let me read it to you. Emily liked to quote Piet Mondrian's aphorism, “If we cannot free ourselves, we can free our vision.”

Aggie: Yeah.

Kathleen: “If we cannot free ourselves, we can free our vision.” How has your vision been freed?

Aggie: Well, that’s a really interesting question. And when we first were married, I went to Australia and I tried to collect some Australian artists because I was just interested in what they did. And I looked for them, and there was no one like Rauschenberg or Johns or Dine. Dine was another person I really liked at first. And I didn’t see anything like that, but I did see some things that were very much from the depths of the Australian life. And it was very much at that time—before we took a trip to Australia and New Guinea, I didn’t go on that part of the trip—I saw how different art was there. And it was something that really made me think, you know, that there’s a lot more to art than just the people that become famous. And I think I thought that now even more because now we’ve collected a lot of things that are not very... they are in the Museum of Modern Art history books, but they’re not especially known artists, and yet they have something that I think makes me interested. And that’s what I’m finding more and more now that I’m not collecting regularly, that I collect for different museums like Cleveland and the Menil, if I used to collect for them, and the MoMA.

Jim Dine, A Little Scissors and a Little Screwdriver, Year of Christie’s sale: 1991, © 1991 Christie’s Images Limited, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Robert Rauschenberg, circa 1965, Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Aggie: But MoMA’s freed itself up and is now doing a lot of things that they didn’t used to do. And especially with PS1, which I think she [Emily] would have been the perfect person to be on the board of PS1. She would have really shook things up a lot. And then what she could do best, which was go to artists who weren’t very famous and weren’t well known and find that they had something to offer too. So that was what I liked about Emily. That she really looked at art through a very much wider lens than most people. She really loved to look and see what was good. And she knew museums. She knew the Albright Knox and the one in Hartford, that she always was friendly to them and they thought they were going to get the collection, but she didn’t...

"So that was what I liked about Emily. That she really looked at art through a very much wider lens than most people. She really loved to look and see what was good."

Kathleen: You’re talking about the Wadsworth Atheneum?

Aggie: Yeah. But she selected things that she wanted and not things that people wanted her to select. That’s why the place that I love best, that Emily was good at doing things in, was the Wadsworth Atheneum. And later on in my life I became a member of their board, but just temporarily. And I think they’ve missed the boat in a lot of ways where they should have been really more recognized because they have terrific things from all periods.

Kathleen: Well, I have reached the end of my questions, Aggie. You’ve been most helpful. It’s been lovely meeting you [laughter] via Zoom, and deep thanks to you.

Aggie: Oh, well, thank you very much. And I was delighted to talk to you, so thank you.

Kathleen: You take care.

Aggie: Okay, thanks. Bye.

Kathleen: Bye-bye

Kathleen L. Housley is the author of eleven acclaimed books, ranging from women’s history to modern art. She has written for numerous national journals and has published articles on women artists and collectors in Woman's Art Journal. She is the author of Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp and Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine. Cover image: Portrait of Agnes Gund by (c) 2013 Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.