Story

Emily Hall Tremaine

as a Patron of Modern Architecture

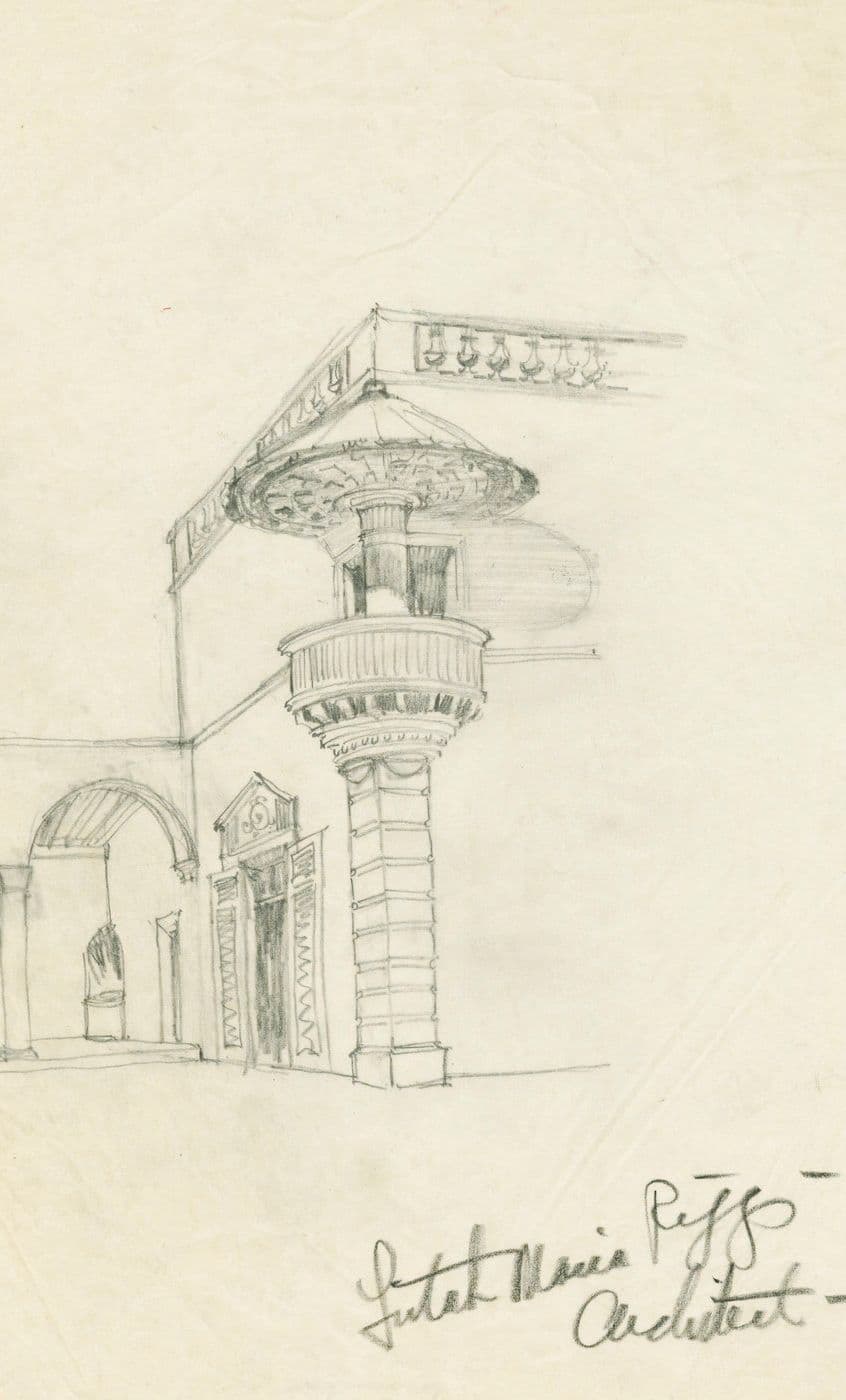

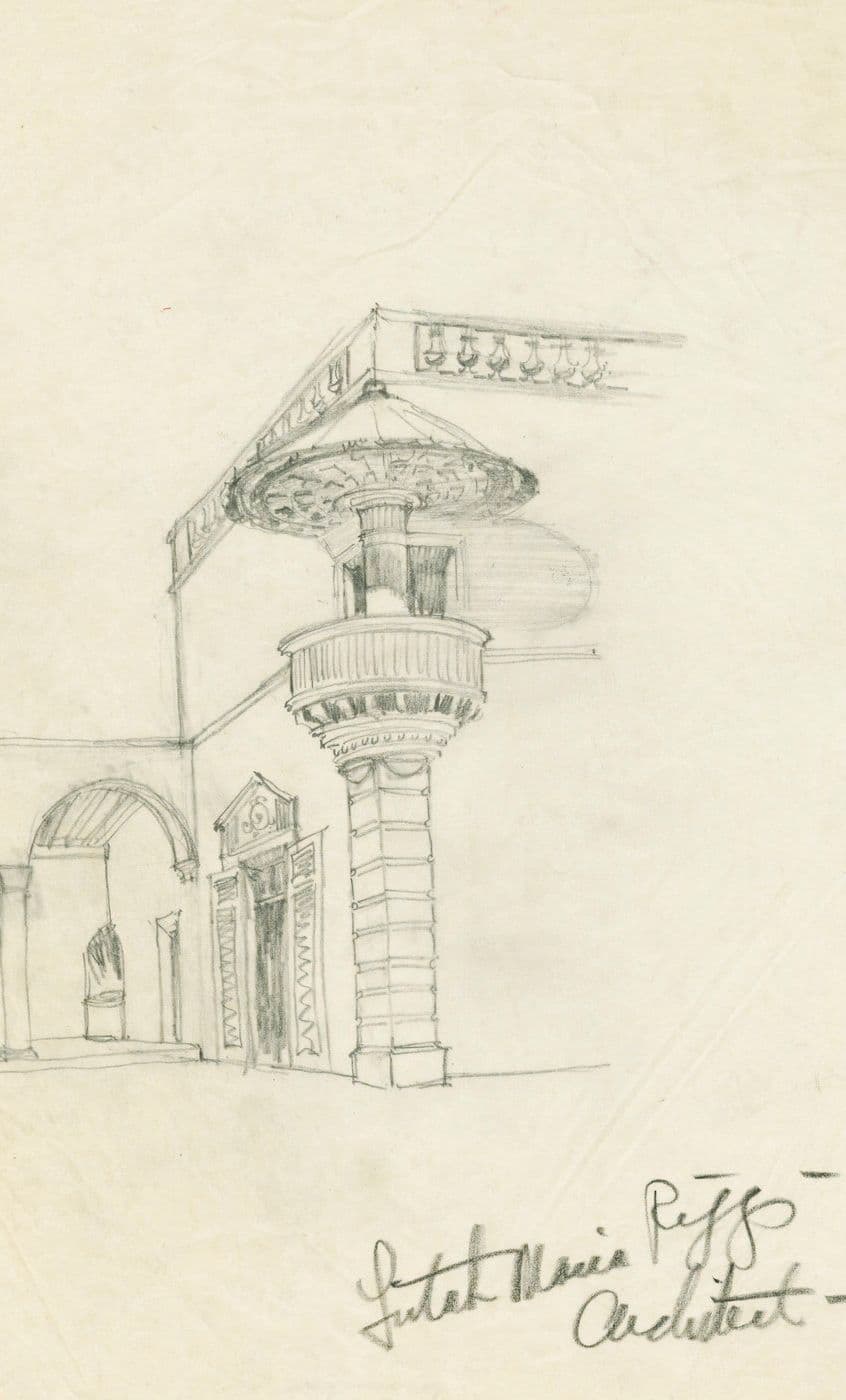

Before there was ever modern art in her life, modern architecture had already captured the attention of Emily Hall Tremaine when she and her then-husband, Maximilian von Romberg, embarked on building a new house in Montecito, just outside of Santa Barbara, California, in the summer of 1936. The couple hoped to rekindle their marriage by creating a new home together; the inspiring cause for commissioning a design came when they went to the pictures that year to see George Cukor’s movie Romeo and Juliet. Little surprise then that early sketches by the Santa Barbara architect Lutah Maria Riggs envisioned a Romeo and Juliet balcony outside of the bedroom of Emily von Romberg.

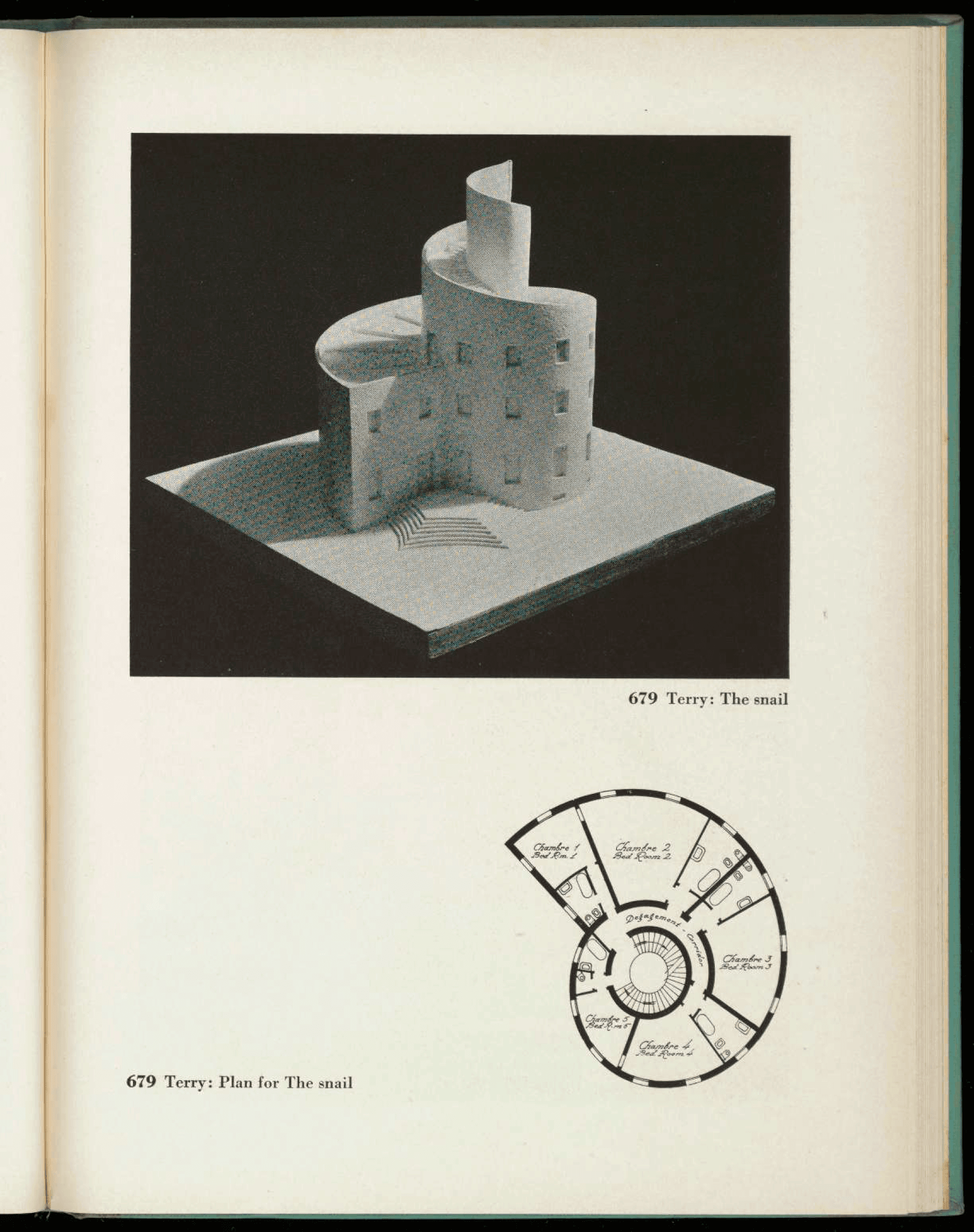

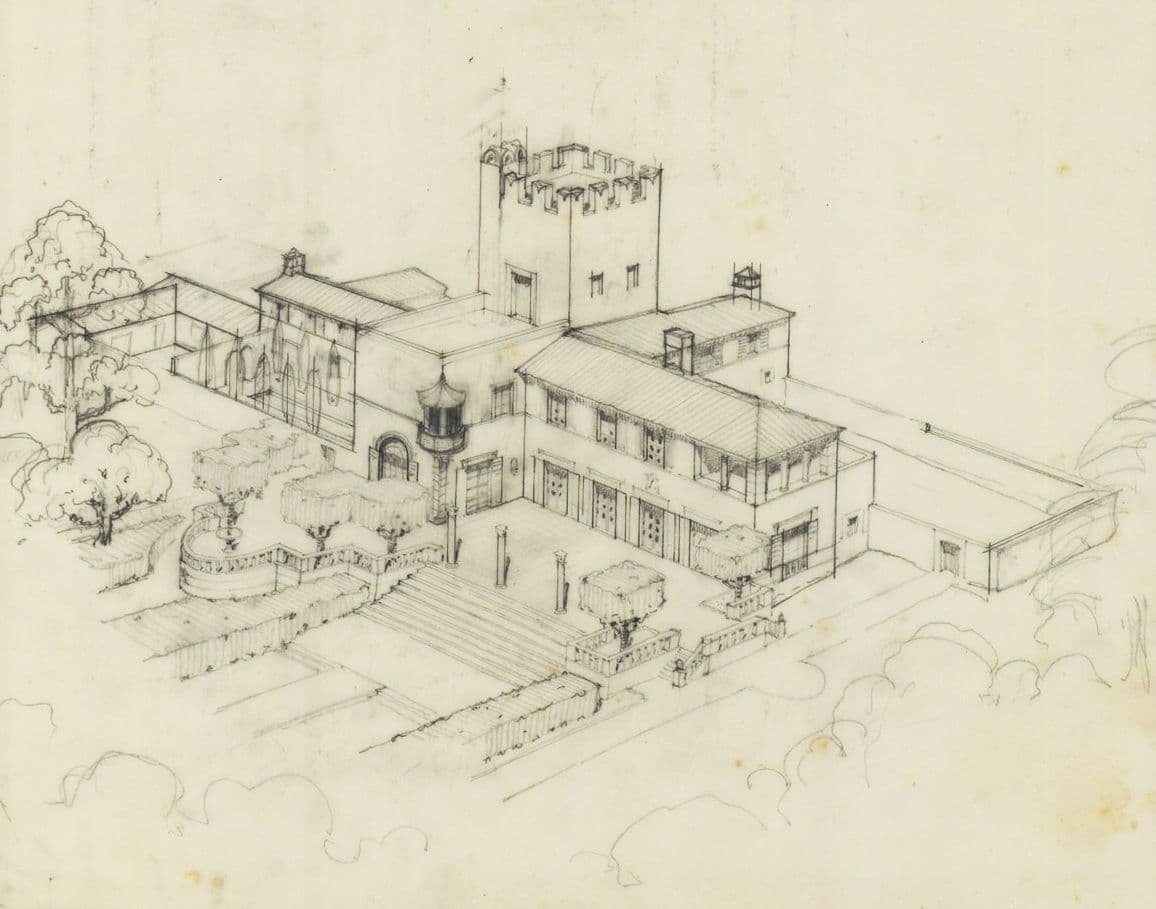

Max Romberg, the son of a German nobleman and an American mother, wanted the new home to be reminiscent of his family’s historical castles and manor houses in Germany, most notably the ancestral castle in Brünninghausen outside of the city of Dortmund. Riggs advised against a sixteenth-century-inspired Italianate Romeo and Juliet villa, an unwise investment in the Santa Barbara area where eclectic revival-style houses existed by the dozens. Emily von Romberg’s vision for the new home only came to her while visiting New York after the construction of the new home had begun. Flicking through the December 14, 1934 issue of Life magazine and scanning a review of the current exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), a photograph of a model of a spiral-shaped house by the architect Emilio Terry made Emily von Romberg realize that she wanted a modern house.

Emilio Terry, model and plan of The Snail. Photo: MoMA publication for the Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism exhibition, p. 202.

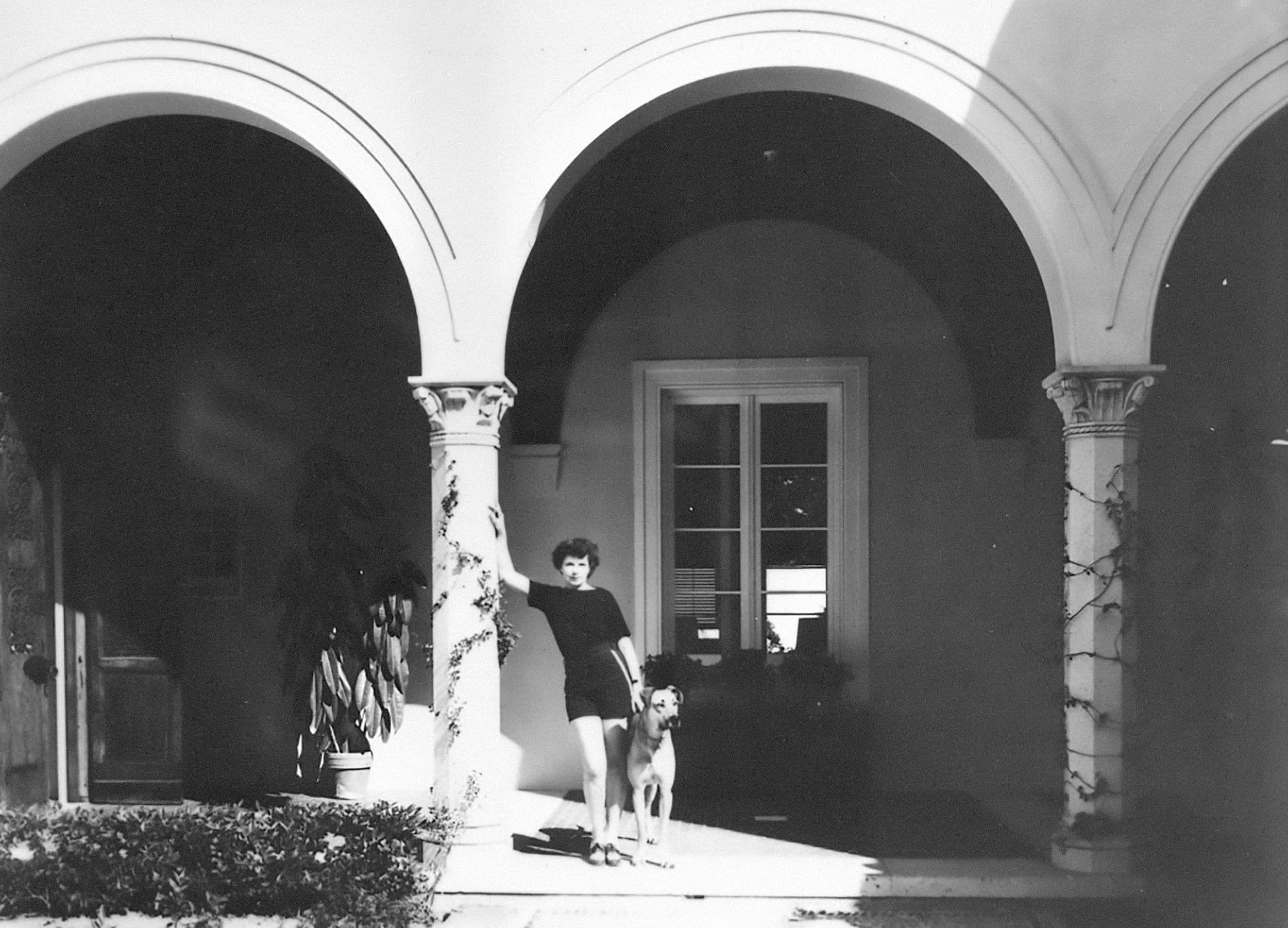

“Brünninghausen,” Montecito, California. Partial view of the completed building, circa 1938. Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

According to Terry, “a building should be ‘a dream come true’;” a maxim that became a rallying cry for Emily von Romberg’s pursuit of a modern home in Montecito and resulted for Riggs in seemingly never-ending redesigns of the original plans while also negotiating carefully between the conflicting ideas for the house by her two clients who later were joined by the modern interior designer Paul T Frankl. With Max von Romberg’s untimely death in an accident on June 4, 1938, it fell to his wife to see through the completion of the home. It speaks to the architectural skills of Riggs that her design masterfully combines references to the ancestral homes of a German noble family with modern and modernist details that hark back to Emily von Romberg’s vision. On the top floor of the house, Riggs and Emily von Romberg created a modernist studio space as Emily’s private realm, to which Frankl’s interior added graceful Art Déco details.

“Brünninghausen,” Montecito, California. Emily von Romberg with a dog in the entrance courtyard. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

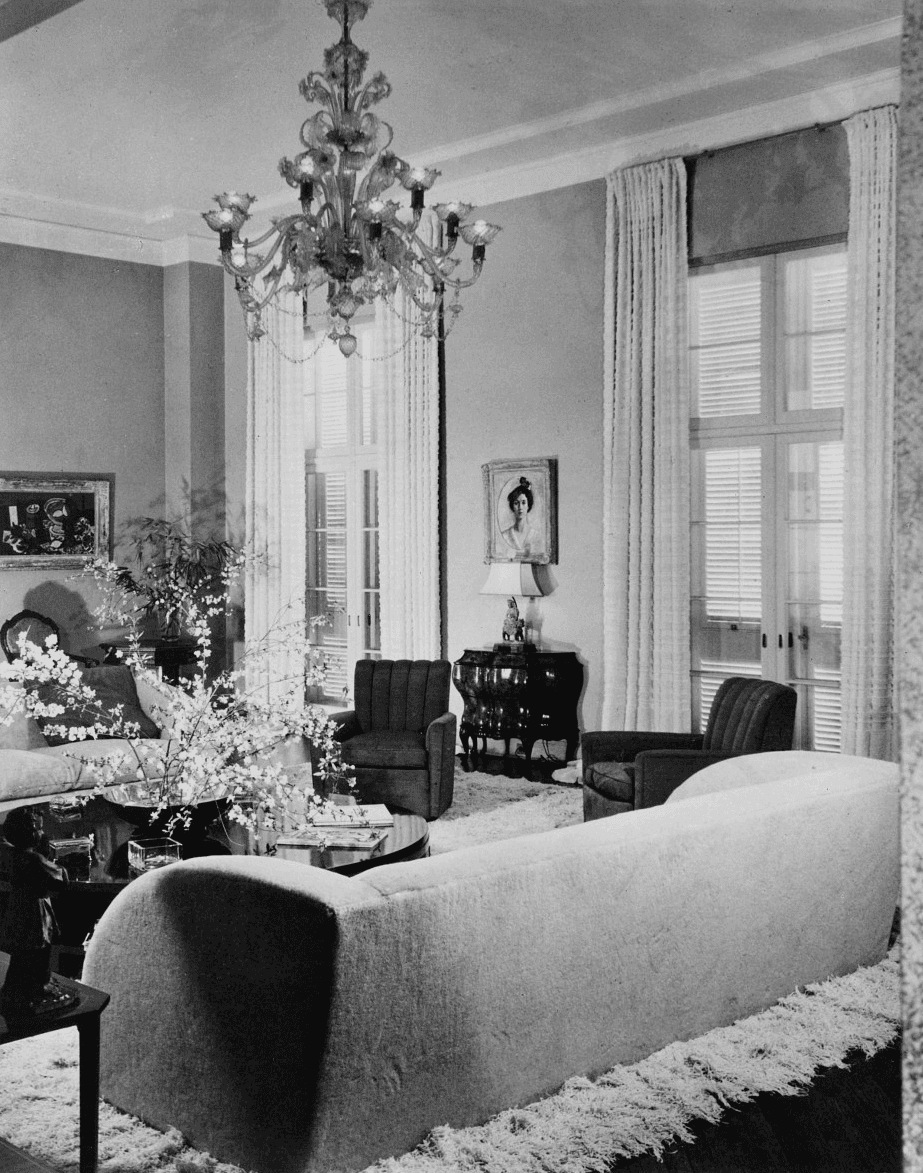

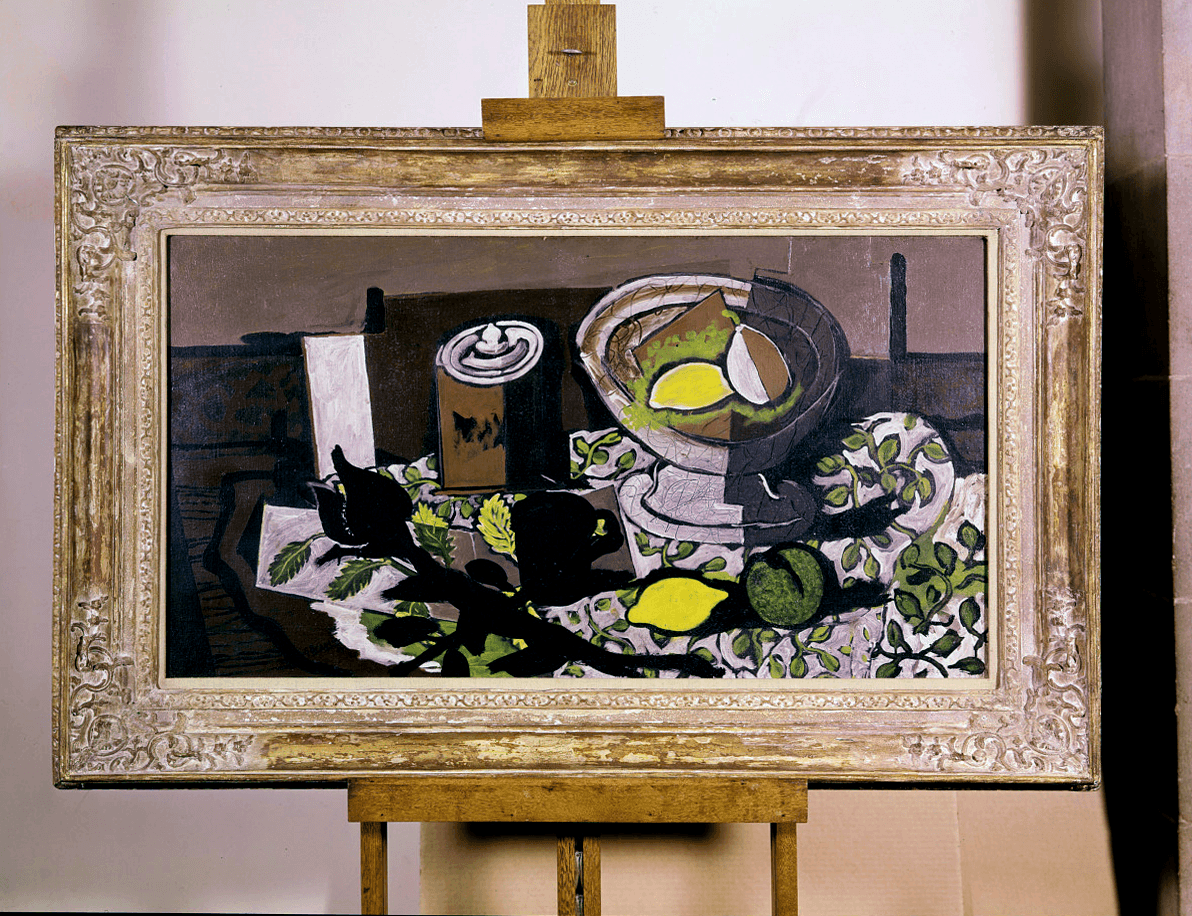

“Brünninghausen,” as the home came to be called, was a decisive step for Emily von Romberg toward defining herself as a modern woman. In 1936, when the design and construction of the house were already in the works, she acquired George Braque’s The Black Rose (1927), her first modern painting around which she would continue building her collection of modern art. After World War 2, she and her future husband, Burton Tremaine, would expand the collection into one of international importance.

…I decided I was really going to be very brave and buy a picture, which was this Braque.

The living room interior with George Braque’s The Black Rose (1927) hanging on the far wall to the left, “Brünninghausen,” Montecito, California. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

George Braque, The Black Rose (1927). Image: Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

“Brünninghausen” also made patronage of architects a life-long commitment for Emily Tremaine, as she became known in modern art and architecture circles. Lutah Maria Riggs, for example, became the go-to architect whenever Emily and Burton Tremaine, but also Katharine and Warren Tremaine, Burton’s brother, had building projects in California and Arizona. In August 1944, Riggs was asked to design a Montecito home for Katharine and Warren Tremaine; only in January 1945 and after Riggs and her clients had already decided on some basics such as the position of the house on the lot, the commission went to Richard Neutra.

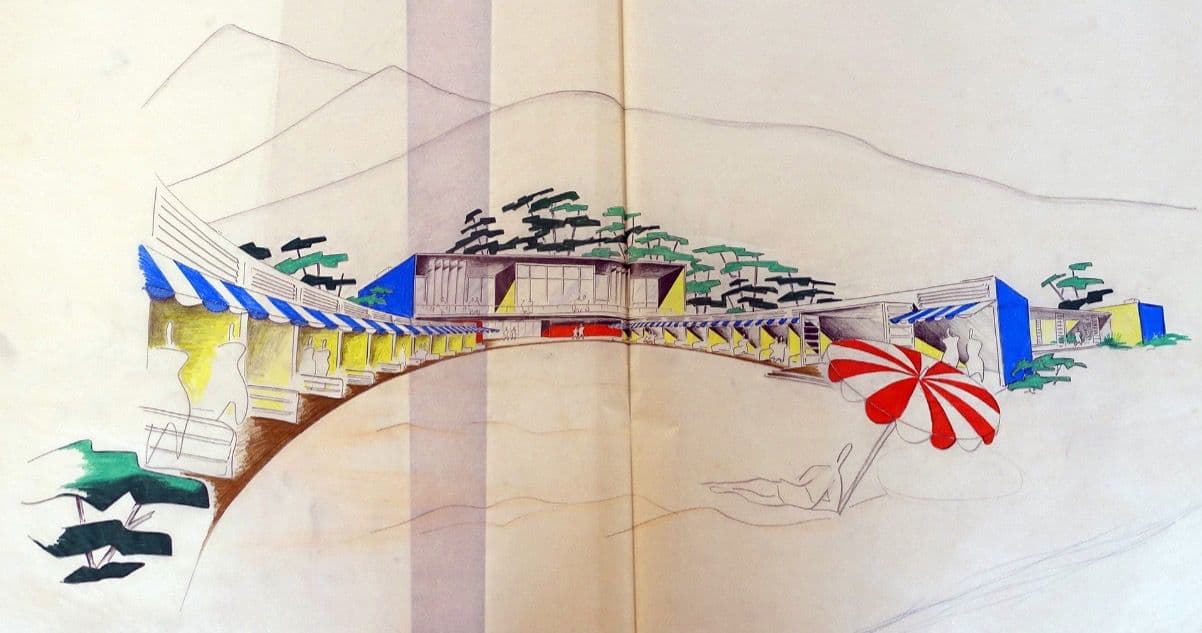

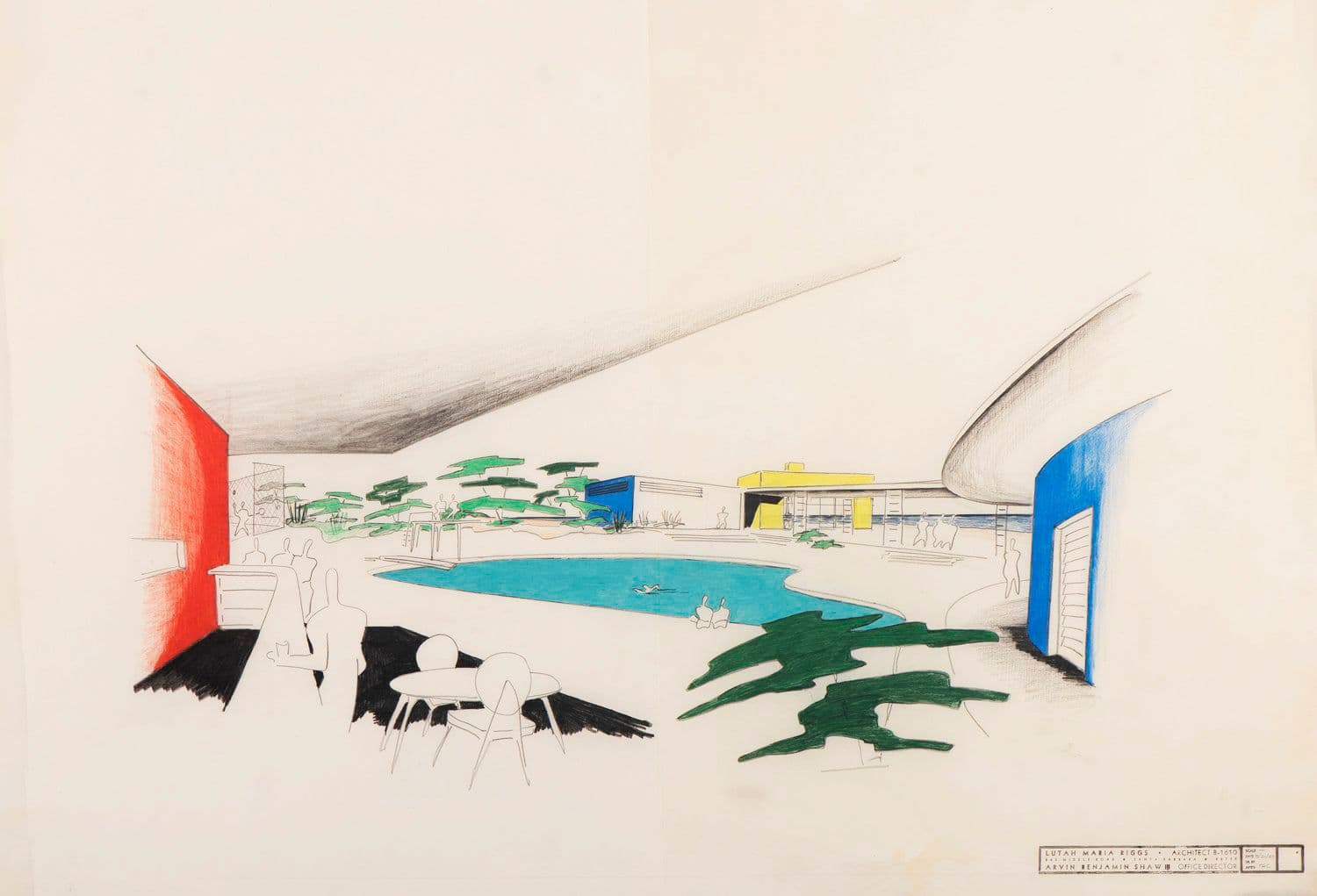

Likewise, Riggs was asked in September 1946 to design a beach house for Emily and Burton Tremaine in Sandyland, California, down the coast from Montecito. By then, Riggs was in partnership with Arvin B. Shaw III, a California native and young Yale University graduate whom Riggs had already employed as a draftsman for “Brünninghausen.” Yet nothing came out of this commission because the Tremaines acquired in June 1947 a much larger property at Serena Beach, much closer to Montecito. They still envisioned a private beach house there but now in conjunction with a privately financed beach club.

Beach Club (not built), Serena Beach, near Montecito, California. Perspectival view of cabanas with an elevated clubhouse in the background, drawn by A Shaw, n.d. (circa 1947). Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

This was not just a shift in location but also in the choice of architects. Riggs and Shaw were asked to design the beach club, a project that inspired Shaw to create one of his best modernist designs from the 1940s, sadly unrealized. The elegant curves of the rows of cabanas, the freely shaped swimming pool, and the vertical sun louvers in front of all-glass walls speak of Shaw being inspired by the work of the up-and-coming Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. Shaw introduced Niemeyer’s work to Emily and Burton Tremaine when he temporarily worked with Niemeyer while the latter was in New York as part of the design team for the UN Headquarters. The Tremaines instantly grasped the opportunity that a beach house designed by Niemeyer would mean for their increasingly public role as patrons of modern art and architecture. At the least, it would add a stunning architectural design to their collection of modern art, of which selections were shown from the end of 1947 onward in a traveling exhibition entitled “Painting toward Architecture,” even if there were barely any architectural exhibits to display. (See Ungendered: The Women in Painting Toward Architecture.)

Painting Toward Architecture, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

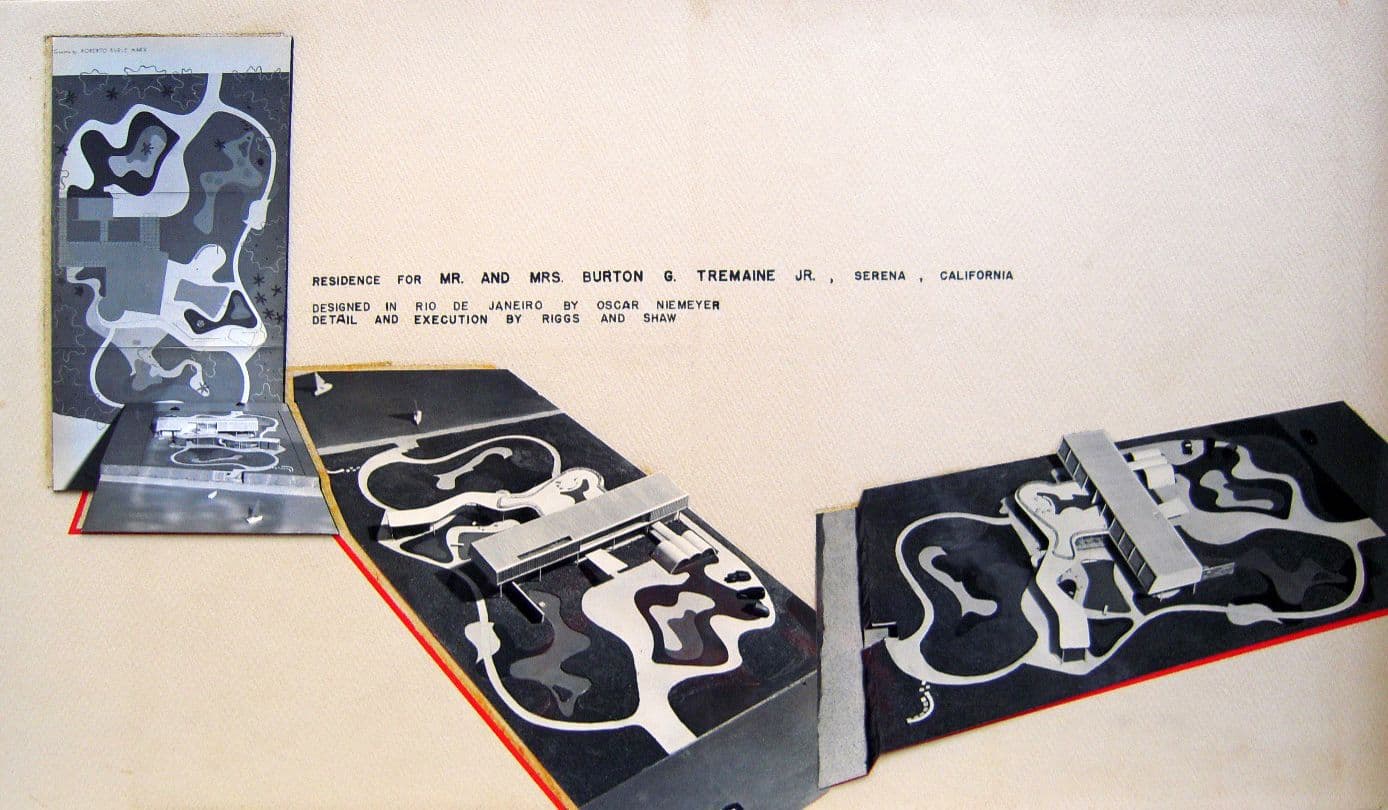

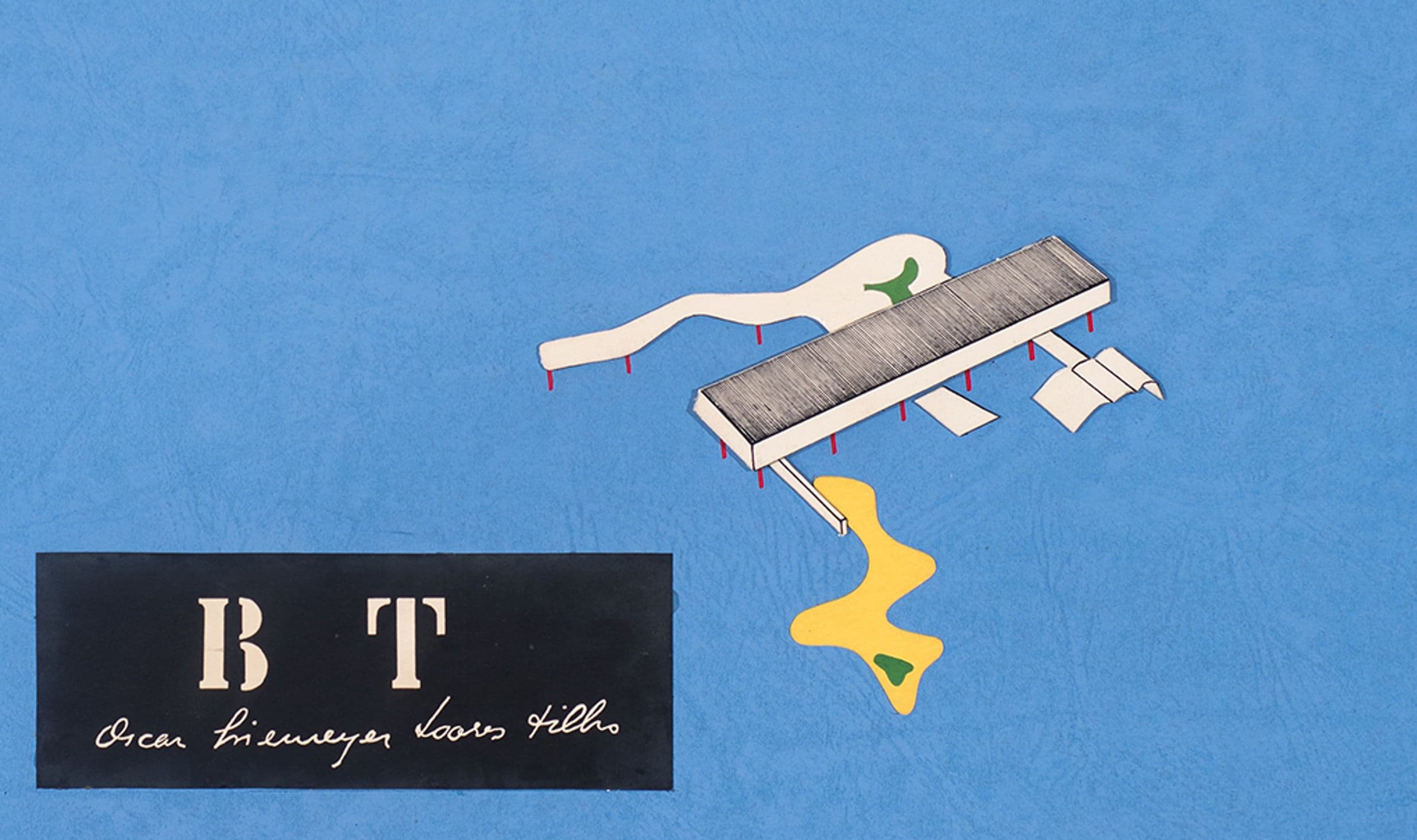

The beach house design was a long-distance project, with Shaw in Montecito being the corresponding architect with Niemeyer in Brazil; Riggs and Shaw were also to act as site architects once the construction began. In April 1948, Niemeyer’s model of the house and his ink drawings arrived together with a garden design by landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx at MoMA in New York via Washington DC as it was shipped as diplomatic luggage. MoMA’s architecture curator of the time, architect Philip Johnson, had a first peek at the design even before the clients, whom he immediately asked whether MoMA could exhibit the scheme. In Montecito, the model was installed in the office of Riggs and Shaw, and the Tremaines flew in from Arizona within a matter of days; their letters to Niemeyer praised the design in the most poetic phrases and words. During the following weeks, selected architects from Los Angeles, including Richard Neutra, who finally was about to complete the Tremaine house in Montecito, and members of the art world in San Francisco made the pilgrimage to Montecito and Niemeyer’s model and drawings.

Page from a presentation brochure showing a photo collage with photographs of Oscar Niemeyer’s design for the Emily and Burton Tremaine Beach house (not built), Serena Beach, near Montecito, California. Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

In the meantime, the Tremaines requested that Niemeyer reduce the house’s size and make it more suitable to the often foggy coastal climate of the building site. While awaiting revised plans, the couple realized that simply by having commissioned this design, their role as leading patrons of the most recent modernist architecture had been assured, whether the house was built or not. Consequently, the Tremaines agreed that MoMA could exhibit the design. The exhibition from February to April 1949 was entitled From Le Corbusier to Oscar Niemeyer, 1929-1949 and proclaimed the beach house to be the successor to Le Corbusier’s ground-breaking Villa Savoye outside of Paris.

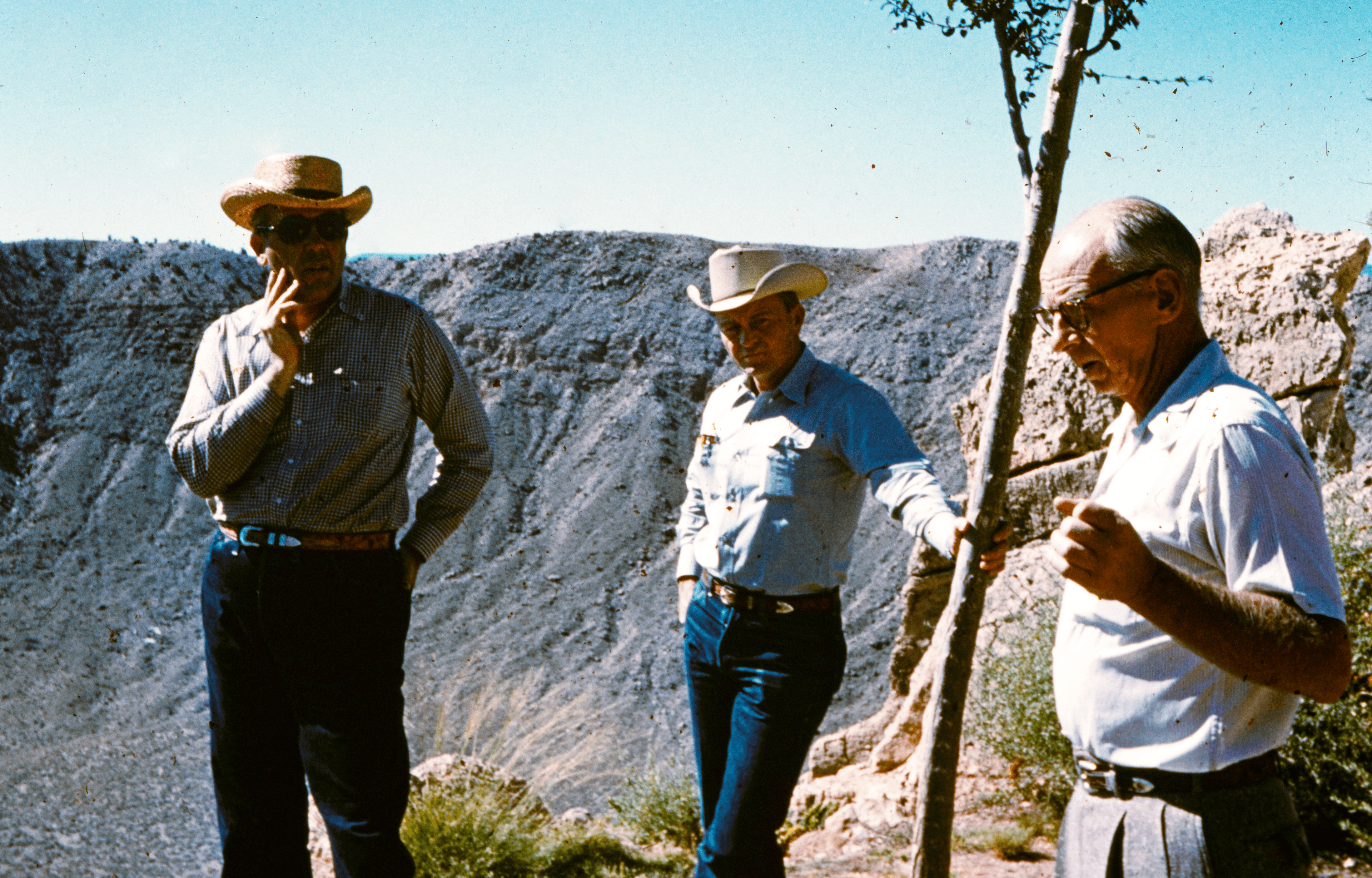

The contact with Philip Johnson at MoMA resulted in more significant designs for the Tremaine family and Emily and Burton Tremaine, respectively. For quite some time, the Tremaine family owned various business interests in northern Arizona, including the rights to exploit the Meteor Crater near Winslow for tourism.

From left: Burton Tremaine Sr. (Jr.), Ernest Chilson, Partner, and George Foster, Museum Curator & Manager, at Meteor Crater, circa 1960. Image courtesy of the Tremaine family.

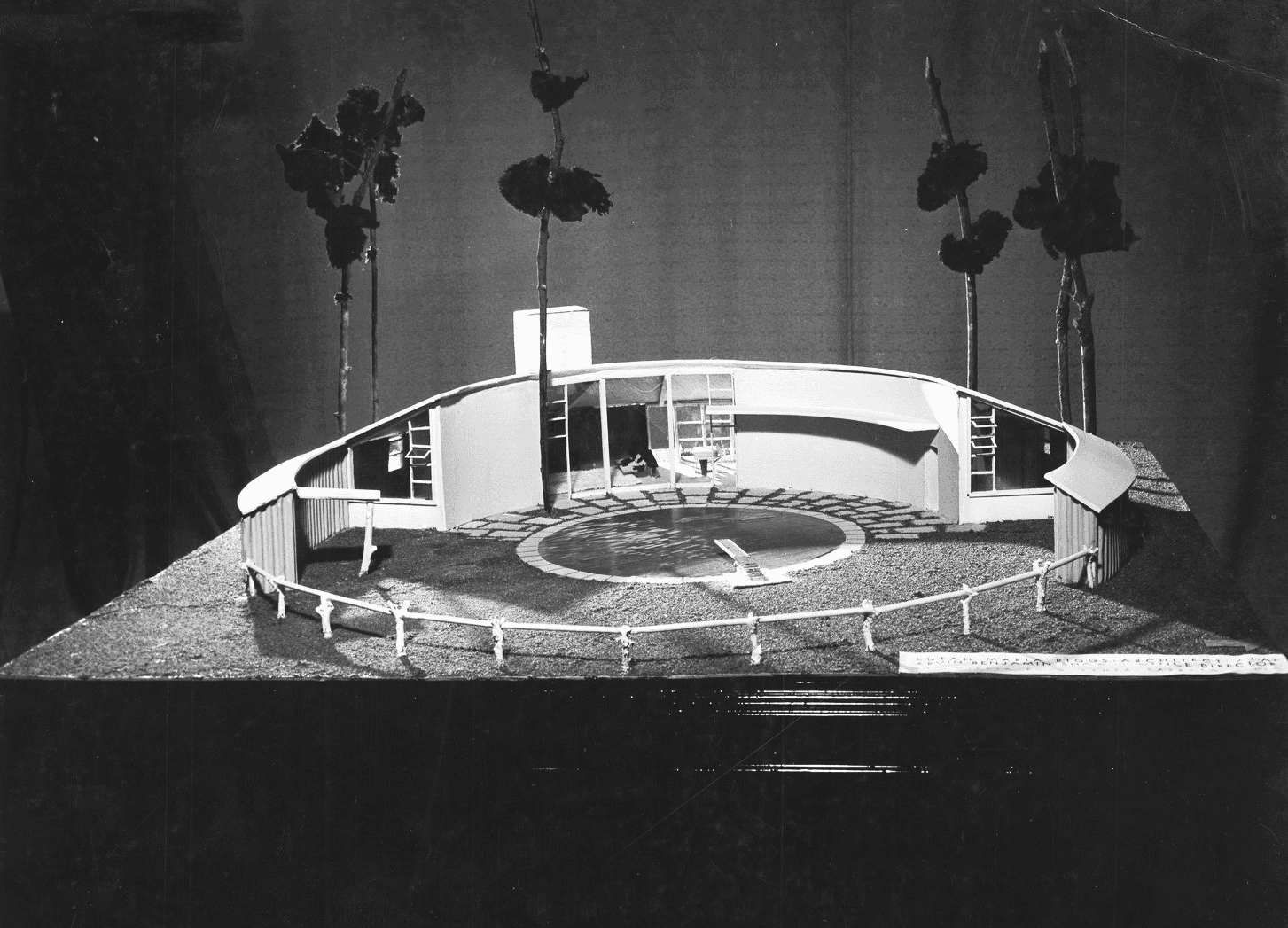

Close to the crater, Riggs and Shaw designed a circular ranch house for Emily and Burton Tremaine, another unrealized design alongside their beach club that was shelved once it had been decided not to build Niemeyer’s beach house. From April 1948 to April 1949, Frank Lloyd Wright worked on plans for a motel and a viewing tower that would have protruded at a daring angle over the crater’s rim; a stunning design that never came close to realization as the clients wanted to erect the project step by step, a business-minded approach that the architect, a true artist, considered entirely inappropriate.

Model of the Emily and Burton Tremaine ranch house near Barringer Meteor Crater, Arizona, circa 1947. Lutah Maria Riggs papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

Philip Johnson was far more accommodating to the client’s wishes when asked whether he would design visitors’ facilities at the crater. Johnson’s final scheme comprised a meteor museum overlooking the crater, an adjacent, oval-shaped open area where cars could be parked behind windbreaking brick walls that, in turn, were interrupted by shops, a restaurant, offices, and staff accommodation, all constructed from brick masonry. Nearby, a tall viewing platform was planned, but this slender brick tower was never erected. Aerial photographs of the slowly growing set of buildings on the rim of the crater illustrate Johnson’s design principle for the project. Each completed building perfected the impression that a large complex of “ancient” structures was gradually excavated from the land.

From the Archives

From the Archives

The Tremaine family also had business interests in Connecticut, where Emily and Burton Tremaine made a home in Madison while maintaining an apartment in New York. In Madison, Burton Tremaine and his second wife had lived in an eighteenth-century colonial house on an estate that also comprised an old barn dating to approximately 1780. In the late 1930s, Burton Tremaine had asked Homer and Alberta Pfeiffer, an architecture couple from Hadlyme, Connecticut, to refurbish the colonial dwelling; from then onwards, Alberta Pfeiffer became the go-to-architect for the family’s building needs in Connecticut, a move that coincidentally mirrors the relationship between the Tremaines and Lutah Maria Riggs in California. Yet, and again similar to Riggs, Pfeiffer also lost out on commissions when competing projects by famous, usually male colleagues came into play.

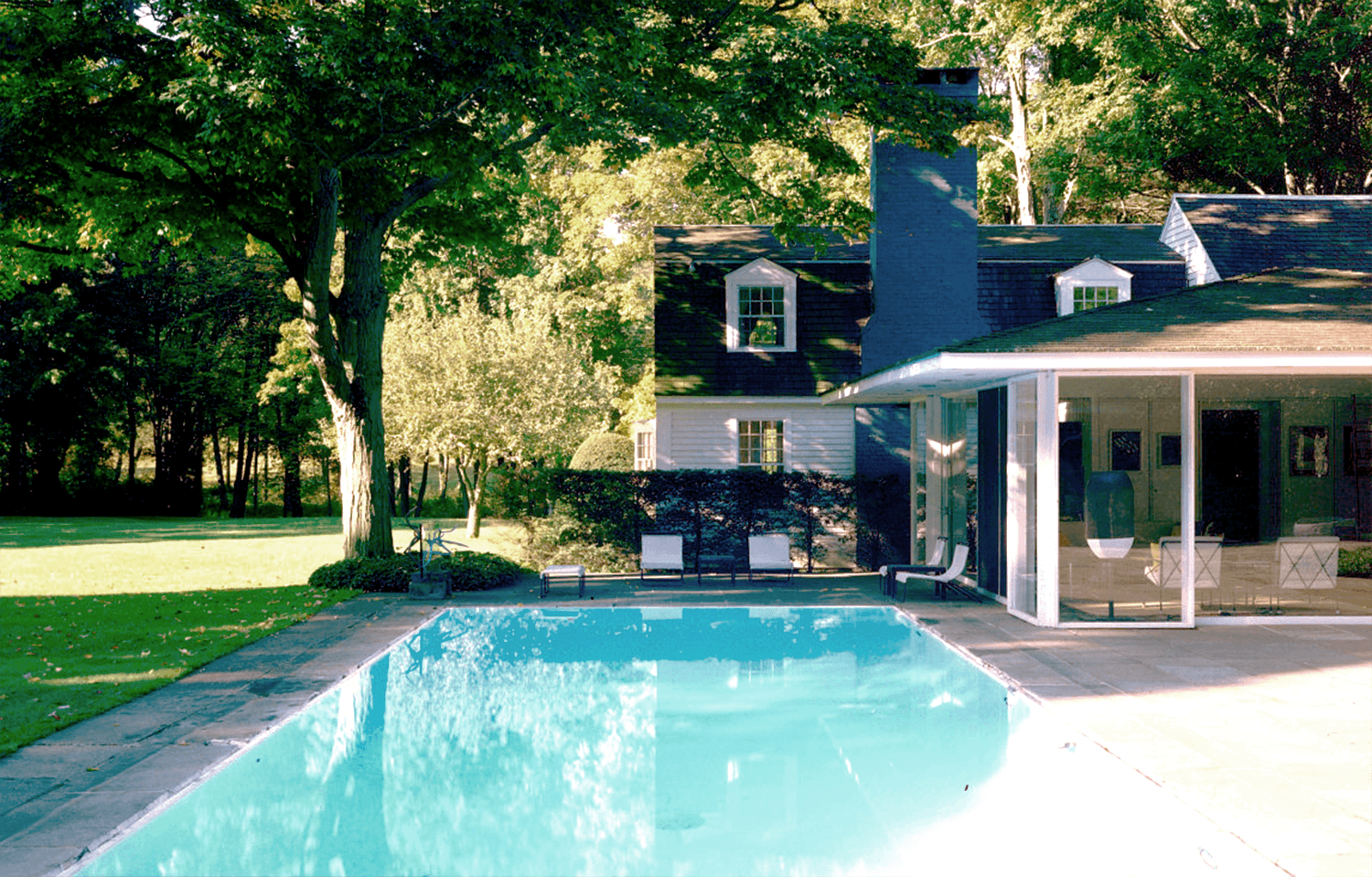

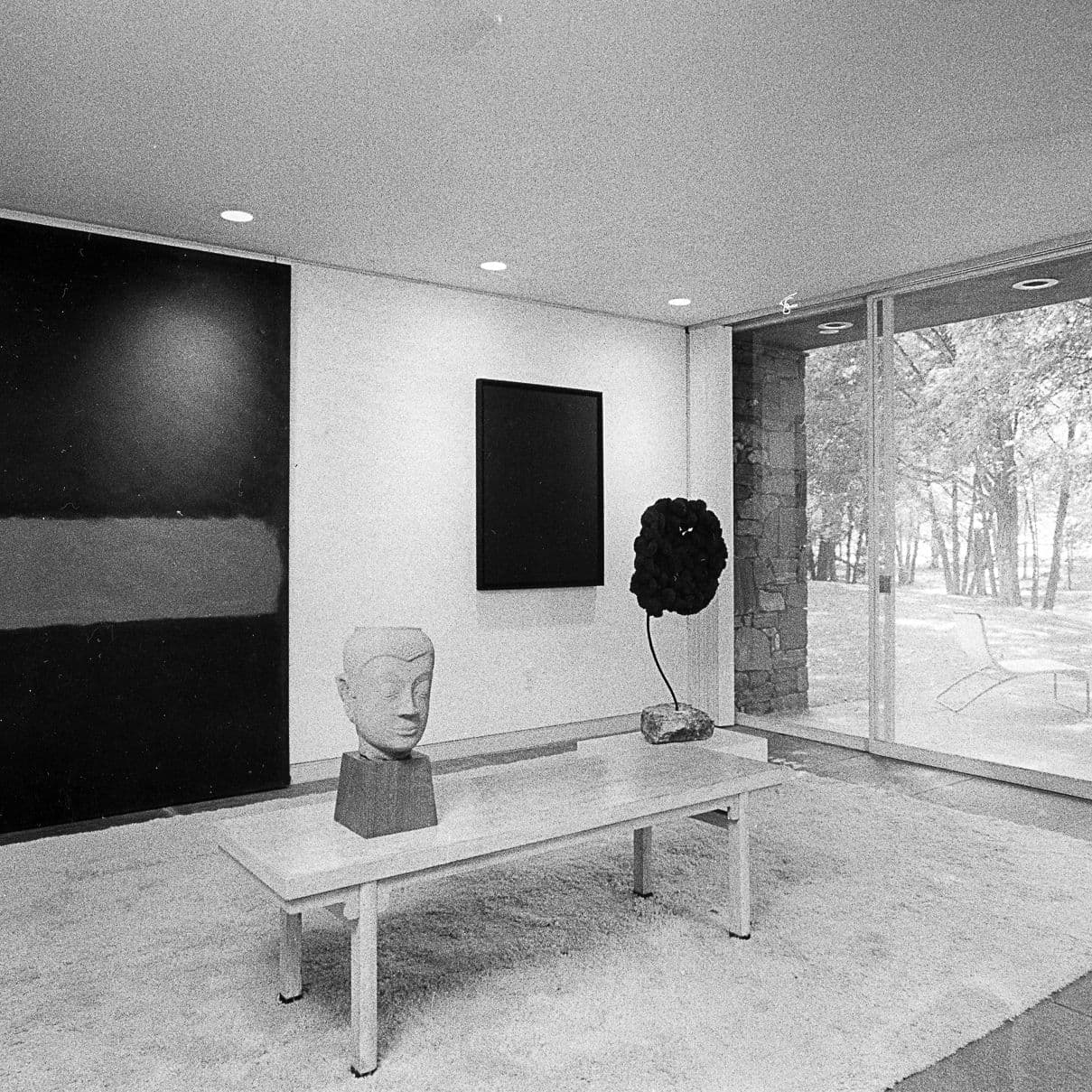

In the early 1950s, Emily and Burton Tremaine embarked on expanding and remodeling the historical buildings on their Madison estate. Pfeiffer was asked to submit drawings for a new garage and storage barn, yet her ideas were not realized. However, Philip Johnson converted the historical barn into space to exhibit modern art and entertain guests; the “Tremaine playhouse” the Architectural Review described the remodeled barn in 1955.

The barn at the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut.

Background: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Foreground: The barn’s interior courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson also extended the colonial home by adding a new entrance foyer on one side and on another side a new pool pavilion, pool, and a generous patio; usually one-story additions with flat or low-hipped roofs, field stone masonry walls, flagstone flooring, and floor-to-ceiling glass walls.

The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Comparable to his archaeological approach to designing the complex at the Meteor Crater, Johnson’s expansions of the Madison Tremaine home appear as almost random additions to an older building, suggesting an assemblage of vernacular buildings erected piecemeal as and when the owners of a home needed more space. That the ownership in the Madison estate was most recently transferred to the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation brings full circle the architectural patronage of Emily Hall Tremaine that began with the California “Brünninghausen” back in the 1930s.

Volker M. Welter is an architectural historian specializing in modern architecture. He is a professor in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Welter is the author of Tremaine Houses: One Family's Patronage of Domestic Architecture in Midcentury America (Getty Publications, 2019). Cover image: Emily Hall von Romberg, circa 1925. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.