Story

Larry Gagosian:

On the Tremaines and Art

Larry Gagosian arrived on the New York art scene in the early 1980s, just a few years removed from selling framed posters on the streets of LA. Thanks to a combination of charm, chutzpah, good looks, and great instinct, Gagosian quickly forged a series of key relationships that would set him on the path to reshaping the art world. One such relationship was with Leo Castelli, the legendary dealer often credited with establishing the contemporary gallery model. Castelli took Gagosian under his wing, introducing the upstart dealer to many of his art world connections, including media mogul Si Newhouse, who would become one of Gagosian’s most important clients.

L–R: Riva Castleman, Calvin Tomkins, Judith Goldman, Toiny Castelli, Barbara Rose, Jasper Johns, Tanya Grossman, Robert Rauschenberg, Buckminster Fuller, Bill Goldstone, Leo Castelli, James Rosenquist, Ed Schlossberg, 1980. Photo: Hans Namuth; Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

But some relationships Gagosian forged all by himself. In 1984, he looked up Emily Hall and Burton G. Tremaine in the Connecticut White Pages and cold called them. He remembers having seen their names for years in exhibition catalogues and knowing they were collectors at the highest level. He had a buyer interested in a Brice Marden work in their collection, even though he had no indication that it was for sale; he called them up, introduced himself, and made the deal.

I knew they were serious collectors at a very, very high level, and they didn't know me. I don't think they’d ever heard of me, which wasn't surprising. And so I was just very, very happy that we just seemed to get along on the phone call. I think they kind of liked my aggressiveness, maybe. I think that appealed to Burton, particularly.

What does he remember most about that first call? “That they took it at all,” Gagosian said with a laugh, during a February 2024 interview in his home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “I don't think they’d ever even heard of me, which wasn’t surprising. And so I was just very, very happy that we just seemed to get along on the phone call. I think they kind of liked my aggressiveness. I was a relatively young art dealer, and I didn’t have that many relationships, so it was just a way of trying to connect. I might not be invited to a cocktail party where the Tremaines were going to be. That was probably not going to happen. So it was a way of, kind of, jumping the queue.”

The Tremaines at their Madison, Connecticut house. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family.

Over the next three years, Gagosian would make dozens more lucrative sales for the collectors. As Gagosian recalls, he met the couple at a moment when they had lost interest in sending their collection to museums, thanks to a lackluster experience donating works to the National Gallery of Art in Washington (something about “a cocktail party and then the art going straight into basement storage”). They were impressed by the booming market for 20th-century works, which seemed to validate their collecting tastes and investing savvy, and eager to liquidate their assets. “Burton was very direct,” Gagosian remembers. “He would say, ‘we’ve got too much art. We want to sell some. We want cash.’”

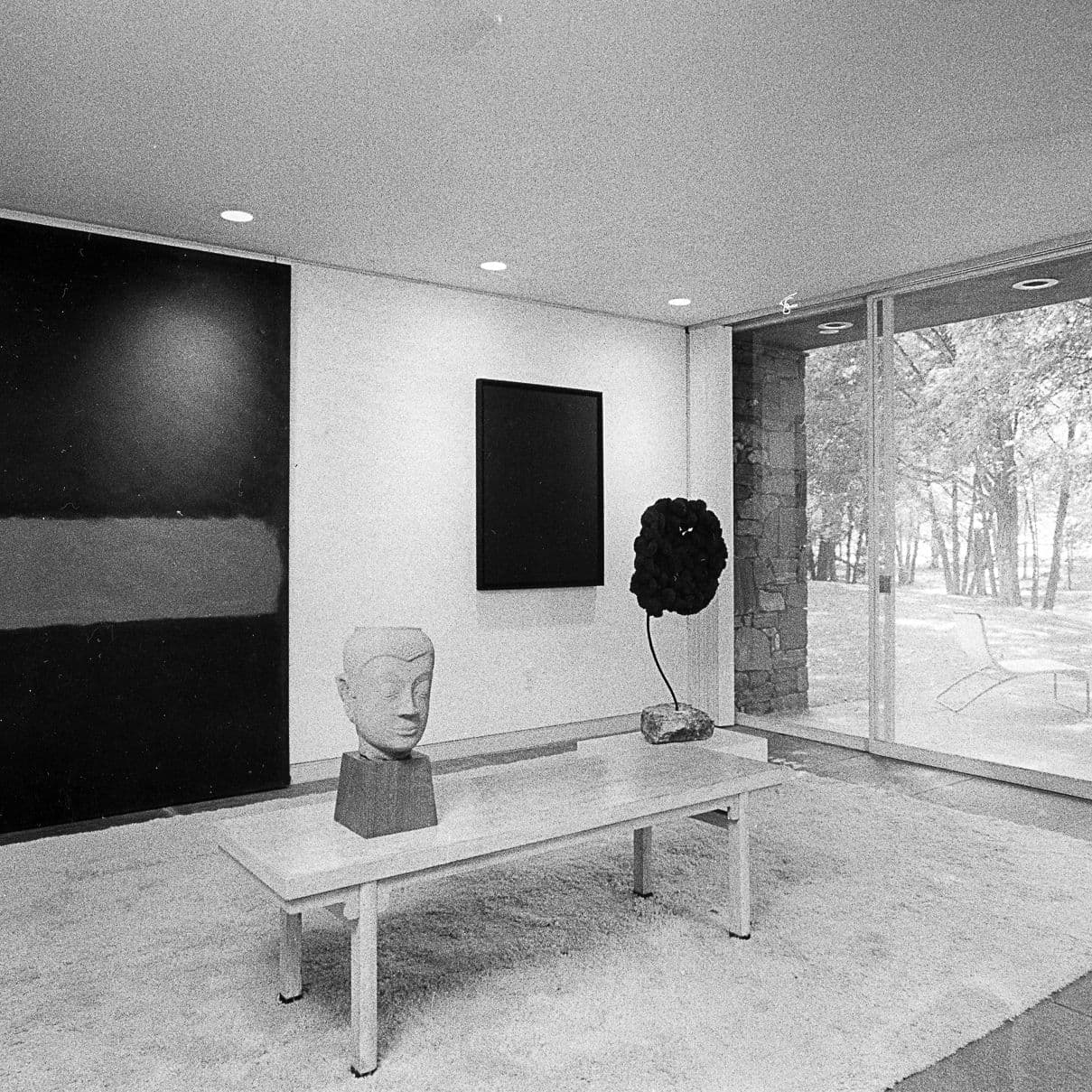

Mark Rothko’s No. 8 (1952), Paul Klee’s Departure of the Ghost (1931), Roy Lichtenstein’s Ceramic Head with Blue Shadow (1966), and Alexander Calder’s Bougainvillea (1945) in the Tremaine’s home. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In this way, they were well-matched. Gagosian had gained a reputation for not playing by the rules of the art world, which at the time (and even to this day) privileged indirect social maneuvers over open discussions about money. Rumors swirled around Gagosian’s meteoric rise, in some cases fueled by the older guard of dealers on whose territory he effortlessly encroached. But the Tremaines were unfazed and in fact seemed to welcome Gagosian’s disruptive energy, Emily in particular. “They defended me,” Gagosian said. “I remember when some people tried to badmouth me, maliciously and gratuitously. She told me about it. She said, ‘you won't believe what [redacted] said,’ and she said, ‘I told him, “well, mind your own business, we love Larry.”’ That was basically what she would say. Maybe somebody else would’ve been swayed by this kind of, little poison in the ear, malicious gossip, but it didn’t faze her.”

My reputation has not really reflected me in a way. I mean, you know, it's like I'm obsessed with money that I'll do anything to make, you know, that I, you know, sell things without authorization. I mean, I've heard it all. They didn't…to them that was just noise. That was just noise. They liked me. They had confidence that when I said I was going to deliver, I delivered. You know, I had a great track record with them, so they were happy to continue to work with me. I mean, I sold, I don't know, 40 paintings of theirs.

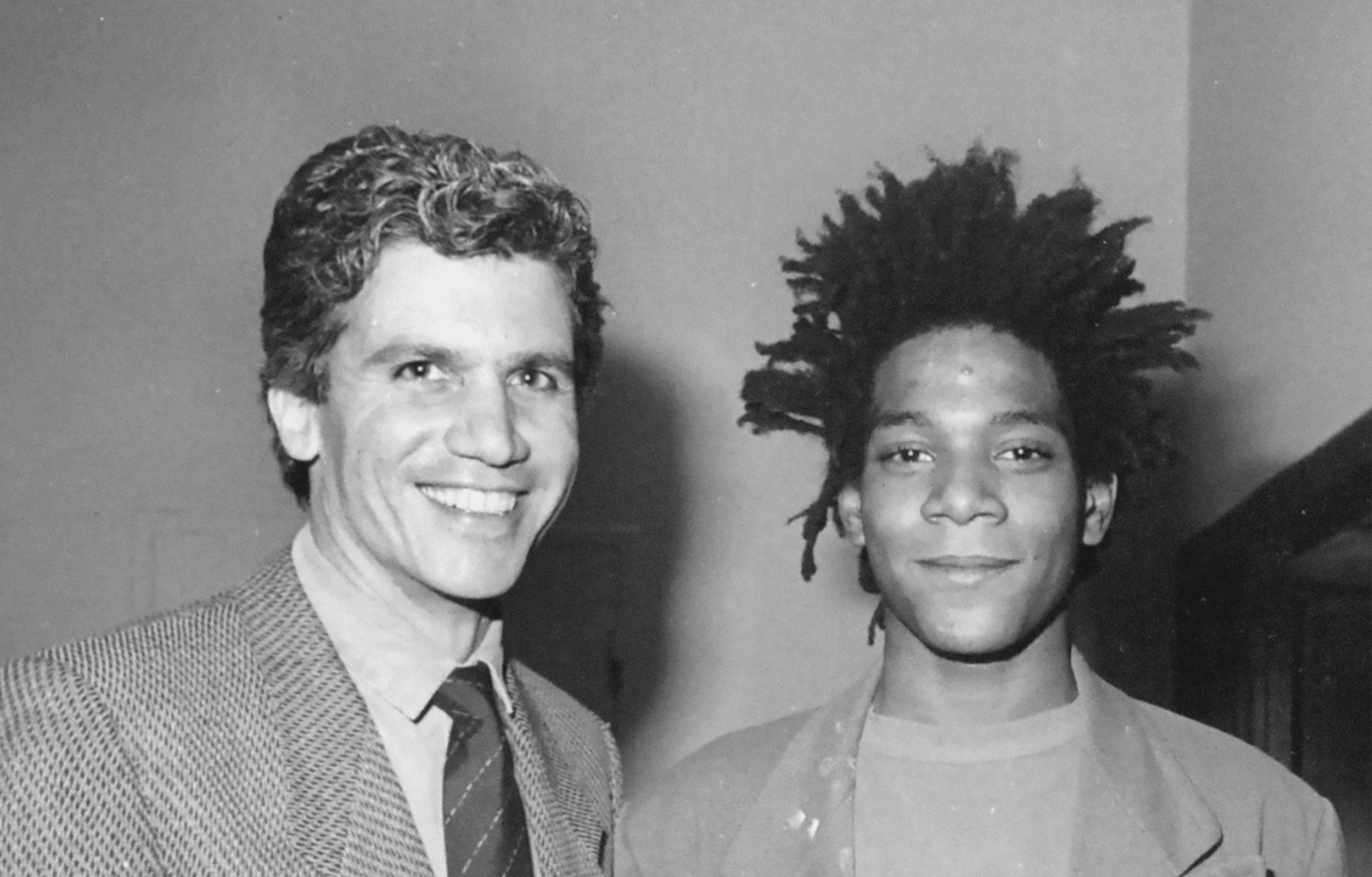

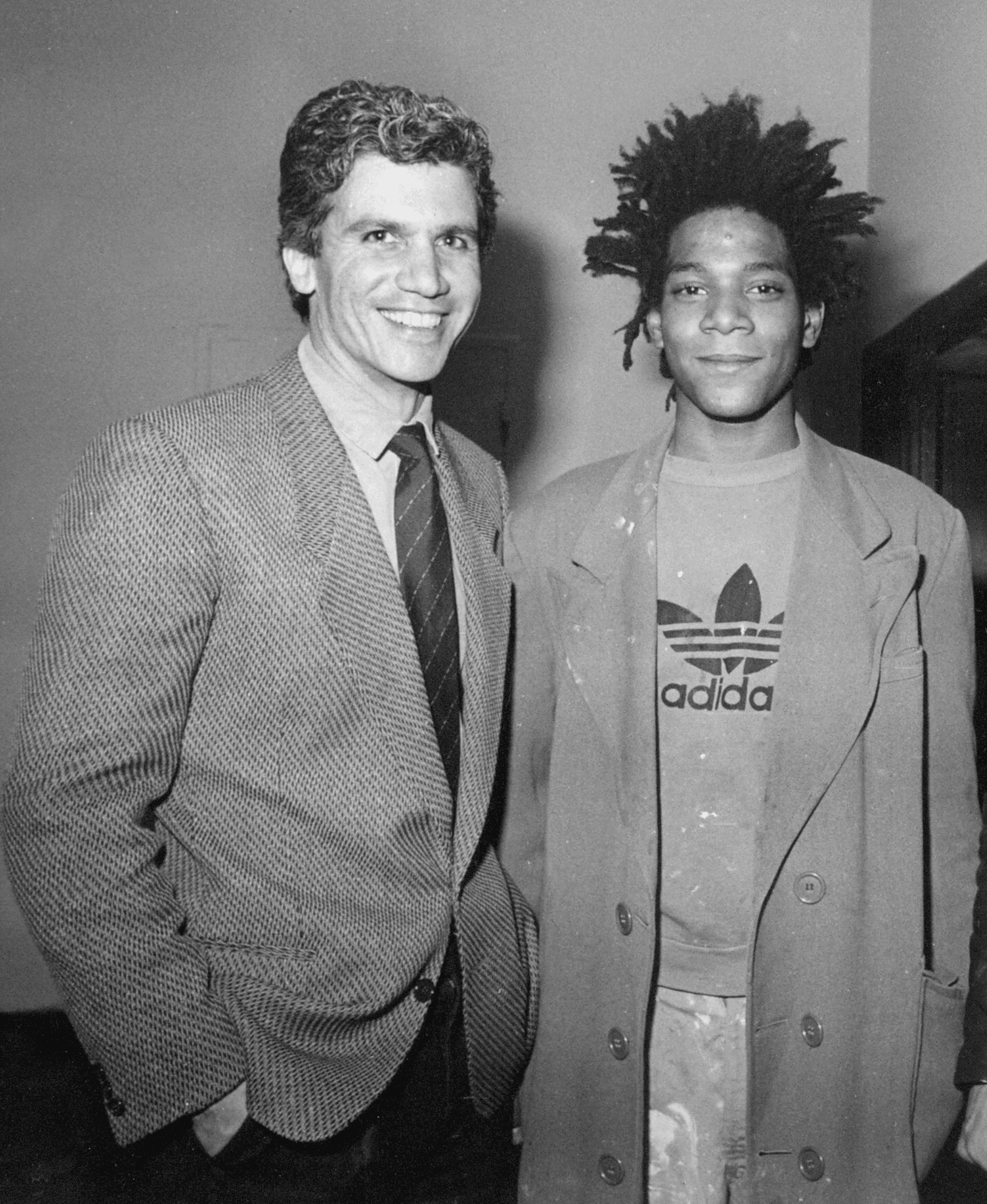

Larry Gagosian and Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, 1983. Photo courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Gagosian had maintained a gallery in Los Angeles, where he famously gave Jean-Michel Basquiat an early big break (Emily bought Basquiat’s Venus from one of his exhibitions), but in 1985 he moved his enterprise full-time to New York, renting a gallery on West 23rd Street in Chelsea long before the neighborhood was a gallery hub. He wanted to open with a splash and asked the Tremaines if he could mount an exhibition of Pop art from their collection. Miraculously, they again agreed. “I mean, it was just very fortuitous,” Gagosian said. “The odds of a collector of that importance sending their paintings to a gallery, to somebody they didn’t know that well, were one in a million. So I was very, very fortunate, and it put me on the map quickly in New York because I didn’t represent any artists at that time. So it was a way of really getting some attention, in a good way.”

I just took a shot with them, and I said would you consider sending, you know, your pop art collection for my opening show? And miraculously they agreed. I mean, it was just very fortuitous. Odds of a collector of that importance sending their paintings to a gallery to somebody they didn't know that well were one in a million.

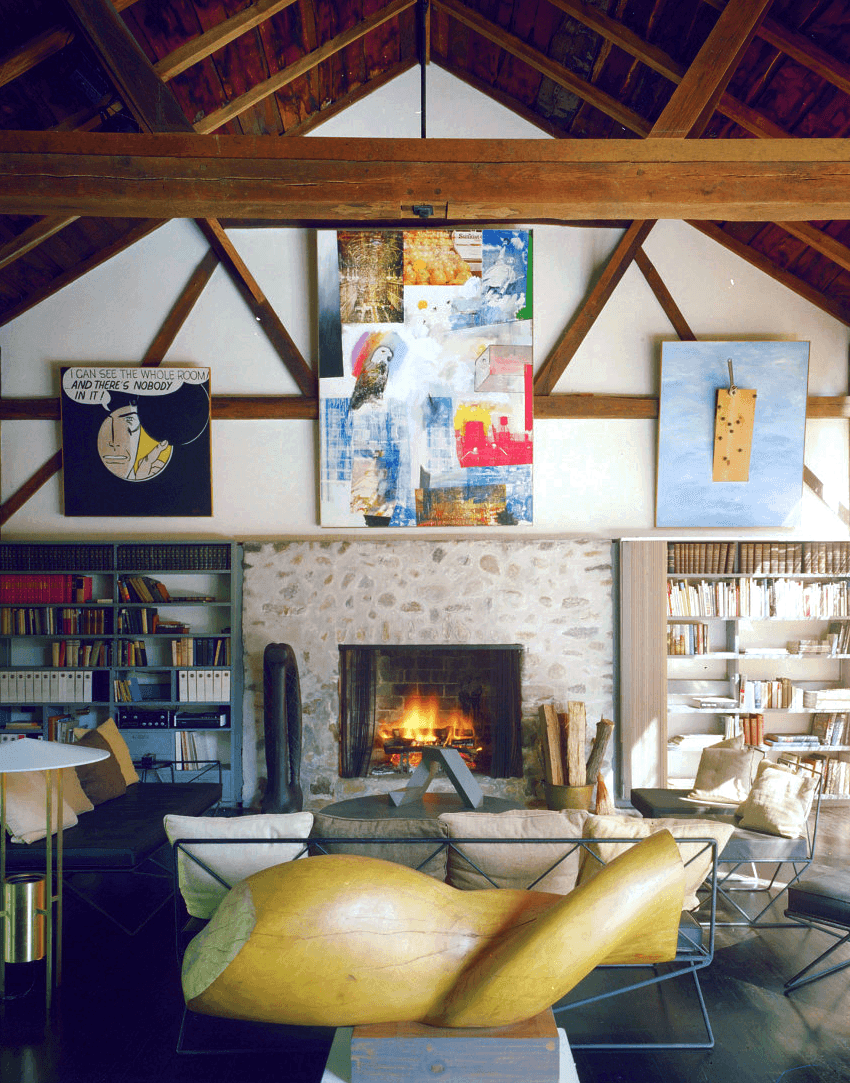

Robert Rauschenberg's Windward (center) in the Tremaine barn at the Madison house, circa 1984. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Gagosian sold a few artworks from the exhibition, including Robert Rauschenberg’s Windward (1963), which went to Ernst Beyeler in Switzerland. He remembers that the Tremaines were not particularly concerned with where their works ended up, so long as they would be seen and appreciated (and paid for). “She figured anybody who wanted to spend that much money for a painting would probably take care of it,” Gagosian said. “It wasn’t like selling a puppy.”

As it became known that he was selling for the Tremaines, Gagosian felt that the transparency actually worked in his favor, making it more of a straightforward business based on trust and less of a game of secret rules and hushed negotations. “I find it’s better when you’re transparent,” he said. “Because then you’re just…your cards are on the table. And I’m not worried that somebody’s going to call—if I’m offering somebody a painting from the Tremaines—it didn’t concern me that they might just call the Tremaines up and buy directly. I always felt that they would protect me in that regard. So I think transparency is a good word for it. I think it benefited the whole thing. Because I was known as the—if you wanted to buy one of the Tremaine pictures, you call Larry.”

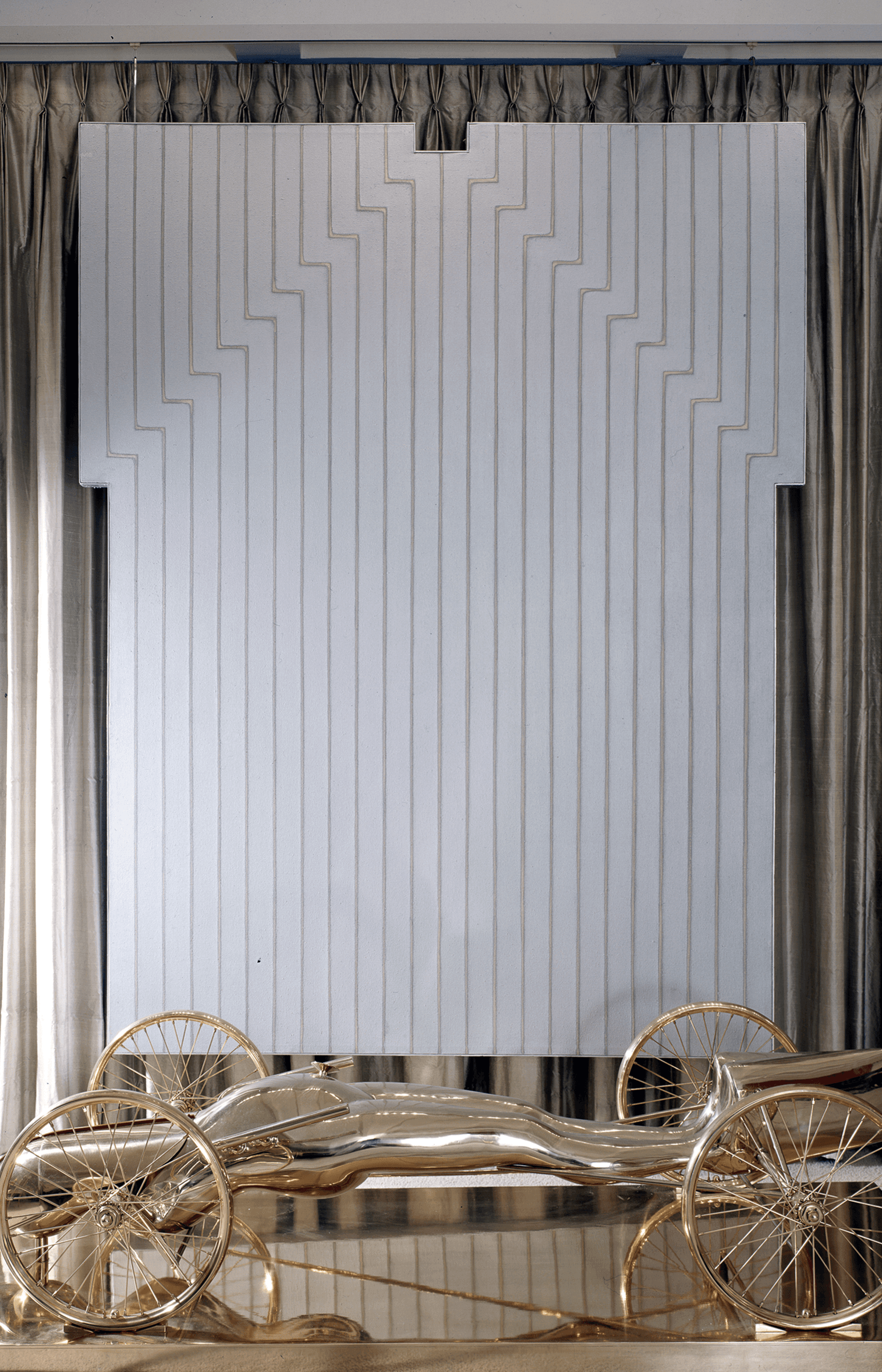

Frank Stella’s Luis Miquel Dominquin (1960) in the home of Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine. Photo courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

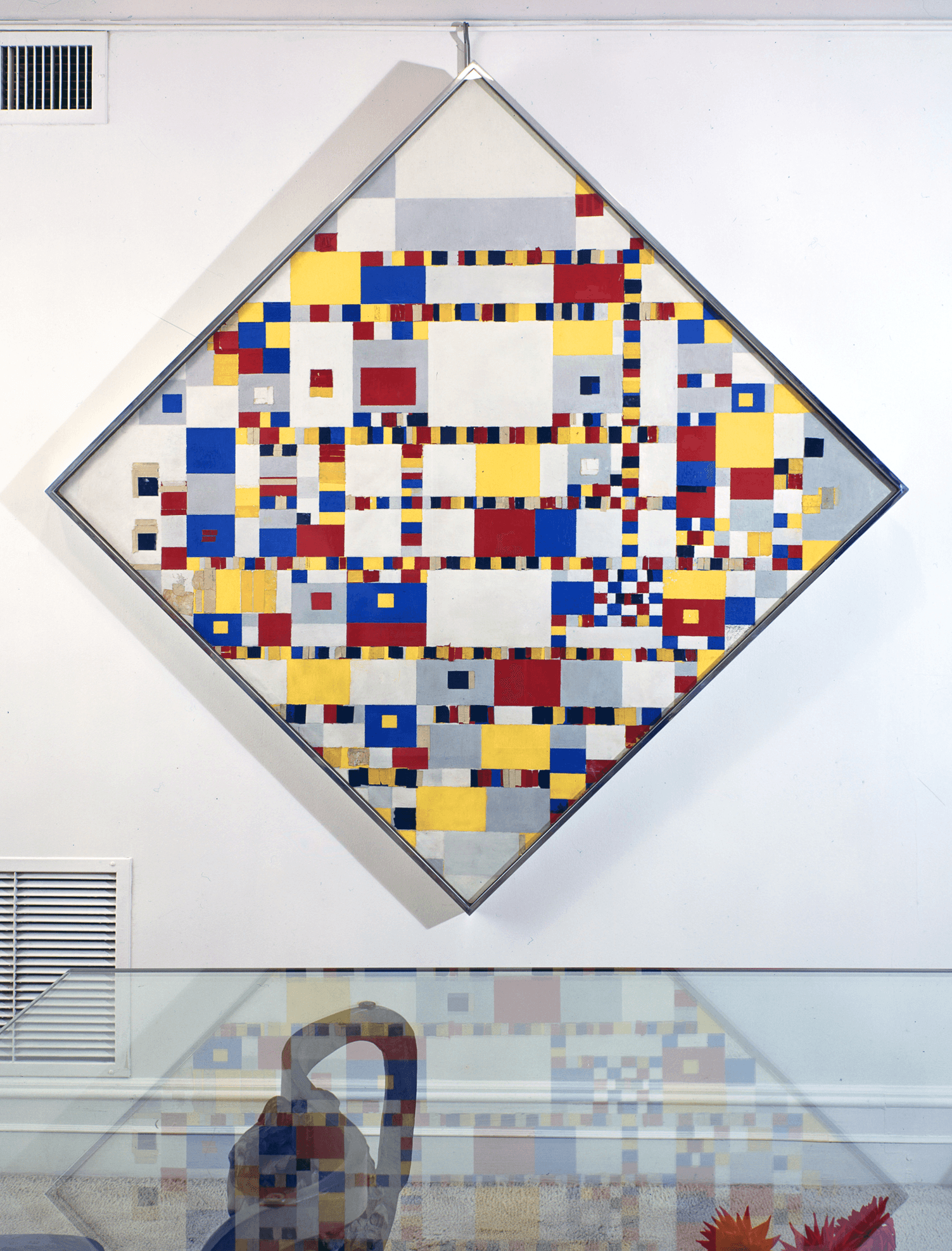

Gagosian sold Alberto Giacometti’s Spoon Woman (1926-27) to Ray and Patsy Nasher in Dallas, and a cubist painting to Swiss dealer Thomas Ammann. A large number of the sales were to Newhouse, including Roy Lichtenstein’s Aloha (1962) and Frank Stella’s Luis Miquel Dominquin (1960)—two sales that broke the $1 million mark.1 According to Gagosian, negotiations around sale prices were natural. “They had great things and they deserved the highest possible price,” he said. “They knew what they were doing. They knew they had valuable art, but they also knew that they wanted to sell it. And you can’t just wait for somebody else to pay $2 million; when you got 1.8, maybe just take the 1.8.” Towards the end of their partnership, Gagosian brokered Newhouse’s purchase of the arguable crown jewel of the Tremaine collection, Piet Mondrian’s Victory Boogie-Woogie (1944), for $11 million. Newhouse later sold the painting to the Kunstmuseum, The Hague, for $40 million.

1—In 1980, before working with Gagosian, the Tremaines sold Jasper Johns’ Three Flags (1958) to the Whitney Museum for $1 million, breaking the record at the time for the highest price paid for the work of a living American artist.

Piet Mondrian, Victory Boogie-Woogie, 1944, in the home of Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine. Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

It was very natural company...we became really close. We'd see each other all the time. We're always in communication because I was actively selling. So we were, you know, sometimes we'd negotiate a better price, or you could bring them in. So that was part of it. And then we just, I enjoyed their company, they were both really terrific people.

Beyond their mutually beneficial business relationship, Gagosian says he became “cozy friends” with Emily and Burton. They would meet for lunches and dinners at Marc Forgione’s An American Place, one of the couple’s favorite restaurants. One time, on their way back to Connecticut, Gagosian recalls meeting them at the oyster bar in Grand Central Station. The business discussions usually took place in their apartment on Park Avenue, and he recalls visiting their Madison “art barn” on a few occasions early on. The Tremaines’ homes were Gagosian’s early introduction to the joy of living with museum-quality art, inspiring him to build and live with his own collection.

The barn at the Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut.

Background: The Tremaines’ home in Madison, Connecticut. Photo: Adam Bartos; Emily Hall Tremaine papers, circa 1890-2004, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Foreground: The barn’s interior courtesy of the Tremaine family. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. © The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“They were great,” he said. “And they were great together. They’d been together a long time. They kind of knew: one would talk, the other would listen…It was a wonderful relationship. For me, it was a gold mine on many levels. And the personal was part of that.” Emily would share stories of her experiences with different dealers and artists, as well as her philosophies of collecting. She told him that she believed Andy Warhol was the greatest artist of her generation. Gagosian recalls that every Saturday, Emily would visit galleries with her close friend Agnes Gund, and that the two of them influenced each other’s collecting. She was equally happy to tell him who to avoid. “She was quite outspoken,” he says. “If she didn’t like somebody, she was very blunt.”

When Emily died in 1987, after a long battle with emphysema, it was like losing a member of the family. “She was a wonderful, wonderful person,” Gagosian said. “Extraordinary mind and she had a kindness about her also. She was a lovely human being, really lovely. And wicked sense of humor, wicked sense of humor.” Long removed from any business dealings (the relationship ended when the remainder of the Tremaine collection was sent to auction in 1988 and 1991), Gagosian says the Tremaines come up frequently in conversation, particularly in recent years as he has been asked to reflect on his career and the development of his transformative business, which now includes 19 galleries around the globe. Without hesitation, Gagosian says he owes a tremendous amount of his success to the Tremaines having trusted him so early in his career. “It was a great relationship for me, and I’m very lucky, very lucky to have had them in my life.”

Jared Quinton is the Emily Hall Tremaine Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. Cover image: Larry Gagosian and Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, 1983. Photo courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

Explore More Stories

Creating Impact

The Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation

Established in 1987 by Emily Hall Tremaine, the foundation seeks and funds innovative projects that advance solutions to basic and enduring problems. With an overall emphasis on education, principally in the United States, it contributes in three major areas: the Arts, Environment, and Learning Differences.